The last few days of June were hectic across the broad expanse of Russia as demonstrations and protest marches filled the streets of cities and towns in a demonstration of the dissatisfaction of the Russian public, primarily the young, with the levels of corruption in the Russian political and economic systems. There had been extended demonstrations and protests against corruption earlier across Russia in May 2017.

These were a reaction to the airing of a documentary on the subject which highlighted the corrupt gains of Prime Minister Medvedev. The documentary was created by Russian opposition politician and 2018 presidential candidate Alexei Navalny and his Fund for the Fight Against Corruption.

On March 2, Navalny released his most recent and explosive report, exposing in damning detail prime minister Dmitry Medvedev’s expansive estates and extravagant sneaker collection. The 45-minute film profiled the lifestyle excesses of the diminutive prime minister and revealed his hidden and presumably stolen wealth compared to Medvedev’s declared annual income of $132,144. The video version of the report has now been viewed more than 22 million times.

In late March, Navalny was able to bring thousands of people into the streets in anti-corruption protests. And then he called for even larger protests on the June 12 anniversary.

These protests by ordinary citizens are relatively new but the corruption in Russia is not new at all. The current level of corruption is a direct product of the system which preceded it. It is the result of continuity, not decline. The protests are becoming more political as the 2018 elections approach but the system of domestic crowd control inherited and improved on by Putin make the creation of a ‘coloured’ revolution in Russia unlikely. The protests of the young and the dissatisfied democrats in Russia are serious, but the ability of the United Russia repressive system to manage dissent, with increasing brutality, seems unlikely to be dislodged by protests.

However, there are two groups in Russia which Putin and his associates fear more than the youthful protestors; two groups who are able to threaten real changes in the system. It is the rising conflict in Russia between the state and the Russian labour movement and the continued unrest in the Russian military which strikes fear in the councils of state. Both derive from the increasingly parlous state of the Russian economy and the absence of liquidity which does not allow Russia to pay its internal obligations.

The Difficulties in the Russian Economy

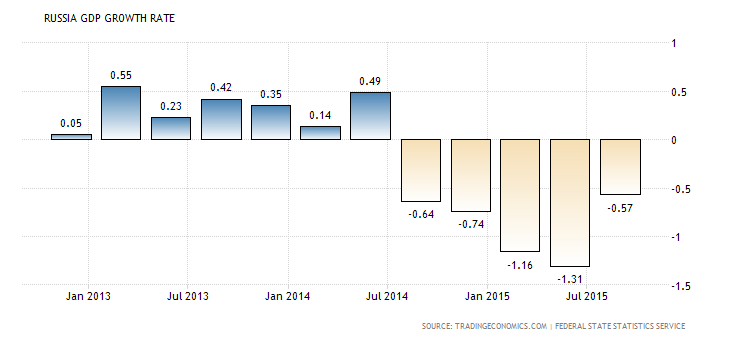

The last three years have been very difficult for the Russian economy. As the price of oil dropped to below thirty dollars a barrel in a very short period, and natural gas prices with it, the Russian economy lost the revenue from its overwhelmingly dominant part of its national income. Even now, with prices up by a small margin, the squeeze on Russia’s economy by low energy prices continues to constrain its revenues. Beyond the fall in the market price for energy Russia also suffered the blow of economic and technological sanctions from the U.S. and Europe as a result of its attack on Ukraine and the seizure of Crimea. The value of the national currency sank like a stone making it much more expensive to import goods. Recently the currency has picked up slightly.

In 2015, the estimated number of Russians living below the subsistence poverty line was calculated to be 20 million — a sharp increase of 2 million since 2014. Countersanctions imposed by Russia, especially on agricultural products, meant that the domestic prices of goods rose even faster, leading to a further decrease in consumer demand. By 2016 the GDP had fallen by around by 3.7 percent and the value of the rouble falling about 127 percent; all components of the domestic demand continues to shrink, and the economy continues to be in recession.

The federal government has already agreed to freeze total spending for three years. To reach an economic-growth target of 4 per cent, authorities need to reallocate funds and raise expenditure by a total of 3 percent of GDP for education, health care and infrastructure. In an attempt to keep the deficit within limits, the government froze wages and pensions, and is cutting investment and current expenditure. As it is prevented by sanctions from borrowing sufficient funds in the international financial markets, and unwilling to embrace privatization, the government is now heavily reliant on its “reserve fund,” which may be soon depleted as soon as the first half of 2017.

Under current conditions, the main reserve fund will disappear in a couple of quarters. In early January 2016, the government ordered all Russian ministries to submit plans for a 10 percent reduction in their expenses. Finance Minister Anton Siluanov warned that without such steps, one of the country’s major reserve funds, which currently has a balance of $59 billion, would soon be empty.

Russia has a second emergency fund, which will allow the deficit to be financed for another 1-1.5 years, that is, providing budget expenditures are stable. No reform program currently implemented is likely to boost economic growth to 4-5 percent next year. That means the federal budget will be short of funds in the next 2.5-3 years at the very least.

The Russian government has little flexibility in adopting an economic program to address the demands made on it. Not only does it have a shrinking economy, a stagnant oil price, a haemorrhage of funds flowing out of its reserves, but a daily bill of about three million dollars a day in its posturing and aggression in the Donbas and Crimea plus another four million dollars a day in the Syrian campaign.

When the Cold War ended, the Soviet Union had a total population of nearly 290 million, and a Gross National Product estimated at about $2.5 trillion. At that time, the United States had a total population of nearly 250 million, with a Gross Domestic Product of about $5.2 trillion. That is, the population of the United States was smaller than that of the Soviet Union, with an economy that was only twice that of the Soviet Union. Two decades later, Russia’s population is about 140 million, with a GDP of about $1.3 trillion, while the population of the United States is over 300 million, with a GDP of $13 trillion. Today, the population of the United States is twice that of Russia, and the US economy is ten times as large.

Global tables of male life expectancy put Russia in about the 160th place, below Bangladesh. Russia has the highest rate of absolute population loss in the world. According to a recent paper by Kudrin and Gurvich for the Economic Expert Group, the Russian population is aging, and Russia remains in the throes of a catastrophic demographic collapse despite the Kremlin’s decision to throw money at the problem. The population posted 14 years of decline before rising by 23,300 to 141.9 million in 2009. However, it is expected to fall to 139 million by 2031 and could shrink 34 per cent to 107 million by 2050.

Eight out of ten elderly people in residential care have relatives who could support them. Nevertheless, they are sent off to care homes. Between two and five million kids live on the streets (after World War Two the figure was around 700,000). Eighty per cent of children in care in Russia have living parents, but they are being looked after by the state.

Drug use in Russia exploded after the fall of the Soviet Union, though heroin addiction had already begun to grow among soldiers returning from Moscow’s ill-fated invasion of Afghanistan, currently the world’s largest producer of opium. Today, Russian officials estimate there are more than a million heroin users, though experts say the true number could be double, if not higher. HIV rates have kept pace.

In addition to axing spending, the government has targeted the pension system. Russian President Vladimir Putin indicated that preparations were underway to raise the retirement age, citing the fact that the country’s lifespan had risen to 71. In 2016 payments to retirees were raised by just four percent, well below the rate of inflation and three times lower than in 2015, resulting in a cut in their real value. Rising costs for food, medicine and utilities, along with pension arrears, are driving Russia’s elderly population into destitution.

The average monthly retirement income for 2016 was just 13,132 roubles, or $166 (about $50 more than the official poverty line for a single person). It was lower, however, for pensioners who continued to work, as their retirement payments are not indexed to inflation at all. In the Siberian city of Novosibirsk, pensioners who went to the post office in January to collect their monthly check were notified that due to “underfunding” and “cash flow” problems, they would not be able to collect their payments at all. Wage arrears have also become widespread. According to official statistics, 2016 began with 3.89 billion roubles in unpaid wages nationwide, а number that has been steadily growing since June 2012. It is still growing.

Corruption is the rule in Russia. Practically every interaction between the citizen and the state (bureaucracy, police, tax bureau, banks, etc.) involve some form of extra-legal payment for what should be a free or regulated service. It is not a surprise that a new wave of labour militancy has exploded across Russia as people have run out of money, pensioners have seen long delays in receiving their pensions, prices have continued to rise and the government seems unwilling or unable to take the kind of action which would relieve these tensions.

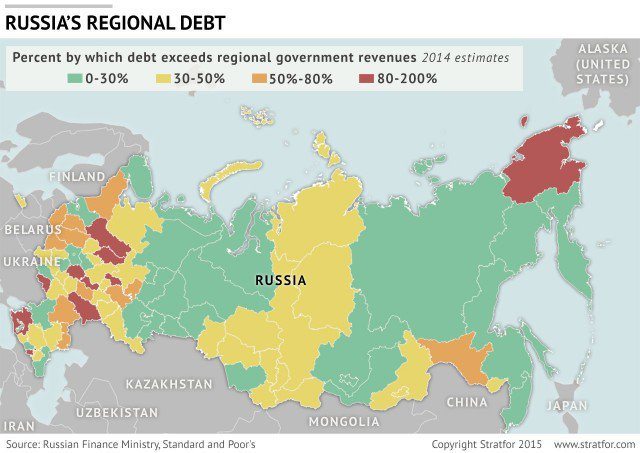

These problems which affect individuals in Russia are compounded by the need for the government to deal with the massive commercial debt owed by Russia’s regions. The list of regions with burdensome debt has not changed since last year. There are 12 regions which hold debt equalling 80 to 100 percent of their revenue, seven hold debt totalling 100 to 120 percent of revenue, Moldova’s debt equals 185 percent of revenues.

The cost to the regions for servicing their debt to the state has doubled over the last three years, and the cost of paying down the debt has risen 360 percent to 2.3 trillion roubles. That total is almost equivalent to the size of the debt itself. The regions are operating with a “cash gap,”. The regions have already received 220 billion roubles, or 70 percent of the 310 billion roubles in cheap federal loans that Moscow had promised them for 2016, according to Finance Ministry data but that enables them to stand still, not to reduce their debts. The fundamental problem is that their nominal incomes rose by only 2.7 percent, whereas expenses grew by 5.7 percent. There only a shrinking or disappearing tax revenue base of income taxes, corporate taxes and property taxes due to the deflation of the economy and there is no place they can go to raise the region’s income.

One of the key areas of social concern has been the shrinkage of the hospital care system which has led to massive hospital closures and a decrease in the quality of medicine in Russia. By 2021–2022, the number of hospitals in the country is likely to drop to the level of the Russian Empire. Between 2000 and 2015, the number of hospitals in Russia halved, dropping from 10,700 to 5,400, according to the Center for Economic and Political Reform (CEPR), based on data from Rosstat. In a report entitled “Burying Healthcare: Optimization of the Russian Healthcare System in Action,” CEPR analysts note that if the authorities continue to shutter hospitals at the current pace (353 a year), the number of hospitals nationwide will have dropped to 3,000 by 2021–2022, which was the number of hospitals in the Russian Empire in 1913.

It is not only the hospital closings which have affected Russian lives, the number of hospital beds also decreased during the fifteen-year period: on average by 27.5%, down to 1.2 million, according to the CEPR’s calculations. In the countryside, the reduction of hospital beds has been more crushing: the numbers there have been reduced by nearly 40%. This is not because there have been alternative health care provisions made; even out-patient clinics have ben closing. During the period from 2000 to 2015, their numbers decreased by 12.7%, down to 18,600 facilities, while their workload increased from 166 patients a day to 208 patients.

The CEPR’s analysts write that the lack of medicines in hospitals reflects another problem in Russian healthcare: its underfunding. The Mandatory Medical Insurance Fund has seen its actual expenditures falling by 6% in 2017 terms of 2015 prices. Compounding these shortfalls of hospitals, clinics and medicines is the suppression of wages among medical professionals. Taking into account all overtime pay, physicians make 140 roubles [approx. 2.30 euros- $2.43] an hour, while mid-level and lower-level medical staff make 82 and 72 roubles [approx. 1.36 euros $1.43 and 1.18 euros $1.25] an hour, respectively. The report continues, “A physician’s hourly salary is comparable, for example, to the hourly pay of a rank-and-file worker at the McDonald’s fast food chain (approx. 138 roubles an hour). A store manager in the chain makes around 160 roubles an hour, meaning more than a credentialed, highly educated doctor” According to a survey of 7,500 physicians in 84 regions of Russia, done in February 2017 by the Health Independent Monitoring Foundation, around half of the doctors earn less than 20,000 roubles [approx. 330 euros $349] a month per position.

Despite the compulsory health insurance scheme by the government, compulsory medical insurance rates do not cover actual medical care costs, which means that patients have to supplement the insurance coverage with cash. The report cites the fact that a basic blood test costs around 300 roubles, whereas outpatient clinics are only reimbursed 70 to 100 roubles on average for the tests under the compulsory medical insurance. Hence the growing number of paid services. Thus, the amount paid for such a shortfall grew between 2005 and 2014 from 109.8 billion roubles to 474.4 billion roubles.

There is the additional dimension of wealth inequality in Russia. A recent Credit Suisse report showed that 10% of Russians own some 89% of total household wealth in the country. Over the past year this figure has increased by 2%, and is significantly higher in countries such as the United States and China (78% and 73%, respectively). Moreover, 70% of Russia’s adult population is among the poorer half of the global population, with a quarter in the poorest 20%. The average Russian adult has some $10,344 in net assets: roughly $2,000 in financial assets, $10,000 in non-financial assets, and $2,000 in debt. On average for 2016, the wealth of Russians shrunk by 14.5%, due primarily to the devaluation of the rouble.

The Russian government has little flexibility in adopting an economic program to address the demands made on it. Not only does it have a shrinking economy, a stagnant oil price, a haemorrhage of funds flowing out of its reserves, but a daily bill of about three million dollars a day in its posturing and aggression in the Donbas and Crimea plus another four million dollars a day in the Syrian campaign.

The Failure of the Russian Business Model

One of the key aspects of Russia’s inability to address its economic problems comes from the unique business model it has created. Its business structure is seriously flawed. Despite the notion that Communism died with the fall of the Soviet Union, the state, its agencies and its companies are populated by the Undead; the unreconstructed nomenklatura of the failed communist system.

In his book, Capital, Marx wrote that ‘capital is dead labour which, vampire-like, lives only by sucking living labour’. He coined the term ‘Vampire Capitalism”; of corporations whose exploitations ‘only slightly quenches the vampire thirst for the living blood of labour’, and that ‘the vampire will not let go while there remains a single muscle, sinew or drop of blood to be exploited’. What Putin has created is a society of Vampire Communism where the Undead suck the life blood from private corporations and government agencies; leaving drained and powerless structures behind them.

The new and powerful people in charge of these new companies and agencies (the ‘siloviki’) have been almost exclusively drawn from the ranks of the ‘Chekists’. A ‘Chekist’ is a general, if pejorative, term for those who are or once were employed in the security operations of the Soviet state – KGB, GRU, MVD, FSB etc. (the ‘Organs’) Dzerzhinsky’s original agency was the Cheka.

Under Putin, these new ‘siloviki’ have been firmly installed in the corridors of power. Under Putin, the Chekists, primarily the St. Petersburg flavour of Chekist, openly took power as ministers, government advisors, governors, bankers and politicians. There may be as many as six thousand of these Chekists in powerful positions in the Russian state. They are not a united force, nor do they follow a single ‘party line’. There are more factions of siloviki than there were factions of the Trotskyites. They are oligarchs in epaulettes.

What is important about the siloviki is that they have created a system of parastatal corporations in Russia; semi-private corporations controlled by state-appointed directors. Theoretically these state-owned companies are the responsibility of a board of directors and management appointed by the state, but their retained capital and cash-flows are controlled outside of the company structure. This effectively removes the linkage between the individual performances of a private company, a parastal or an industry from the funds it generates. Because of the configuration of the siloviki economy the profits from the various producing entities and service industries are not kept in the name of the generating company or service but effectively put into a central pot (like the ‘obschak’ of the Russian Mafia) for distribution by the political leadership.

This divorce from a direct line between earnings and capital accumulation makes corporate planning a subject of political discussion and debate. This is inimical to the notion of ploughing back profits towards R&D, maintenance and the renewal of plant and equipment. This is the central weakness of the Russian economy and a powerful reason for the stranglehold of the siloviki on the direction of the economy.

This has proved useful when the state wishes to purchase more shares in companies. The state uses mirrors and smoke and fake transfers to acquire companies like Yukos; pretending that these funds have been made available to Rosneft or Gazprom. There are enormous amounts of funds transferring around the Russian economy for share purchases; but no cash. The state can acquire companies this way, but they cannot make them work. Work requires investment in capital equipment; cash for repairs and maintenance; money for research and development, etc. The re-nationalised companies are all competing for the small cash reserves of the state and are dependent on which group of competing siloviki has the ear of the keepers of the purse string.

Many of the previous ‘oligarchs’ are still in business but they have virtually no political power. Russian businessmen and siloviki have been pulling their money out of Russia as fast as they can. Russian flight capital is of epic proportions.

What Putin has created is a society of Vampire Communism where the Undead suck the life blood from private corporations and government agencies; leaving drained and powerless structures behind them.

On-Going Strikes and The Growing Strength of the Independent Labour Unions

This system has made the role of trades unions very difficult. It has always been difficult to be a working-class man in Russia; now it is even worse.

In the Soviet and other communist systems, trade unions played a different role than those in the West. Soviet trade unions had a distinctive relationship to the state. They were government organized, state-controlled bodies which performed “dual functions.” They had management and administrative functions and were also charged to protect and defend workers’ interests. They were designed both to represent the workers and to increase workers’ production. Trade unions controlled housing, day care, health care, access to vacation spots, recreation and cultural areas and, most importantly, social security funds and pensions.

The Soviet working class had made a tacit agreement to trade social security for political compliance, a “social contract.” In this contract, the regime promised full and secure employment, low and stable prices on necessities, a wide range of free social services (day cares, hospitals, schools, etc.) and egalitarian wage policies. In exchange for economic and social security, workers accepted the monopoly of the Party on interest representation, agreed to the centrally planned economy and to the dictates of the authoritarian system. The erosion of the social contract during the late Soviet period led to a system in which there were fewer shared values. The lack of consensus or tradition of discussion on what a society or government should or should not do led to a dramatic rise in labour unrest and political activism.

Unions were organized on an industrial as opposed to a craft basis. There were fifteen industrial unions affiliated to the central union organisation the All-Union Central Council of Trade Unions (AUCCTU). The unions had a state-granted monopoly in their respective industries. This type of organization allowed for maximum Party control and also precluded any choice on the part of union members. The AUCCTU was led by high level Party functionaries; Alexander Shelepin, the former head of the KGB, became the head of the AUCCTU. The labour movement was a key part of the Party’s control of the government and the economy.

The one major labour impact of the post-Soviet political turmoil was the transformation of the state-run unions in 1990 from a constellation of plant level unions into ‘independent’ trades unions. These essentially took over the assets of some of the Soviet labour unions and maintained them for the workers affiliated to these unions. These unions formed the Federation of Independent Trades Unions (FNPR in Russian) in 1990. They included in the bargaining unit both white collar as well as blue collar workers plus middle management.

Since the formation of the Soviet labour system in 1920 there has always been the distinction between the narrow, ‘bread and butter’ unionism best known as the US model and the broader, more political unionism of party, unions and social organizations encompassed in the term ‘professional associations’. In Russian, the pejorative term ‘tred unionizm’ has always referred to narrow economic unionism as opposed to the Soviet term ’profsoiuz’ which covers a far broader spectrum.

The state unions are still operative in Russia but there are also a wide variety of independent unions which have developed which have taken on the role of labour militancy for economic, social and legal rights for Russian workers. Their militancy has posed serious and immediate problems for Putin.

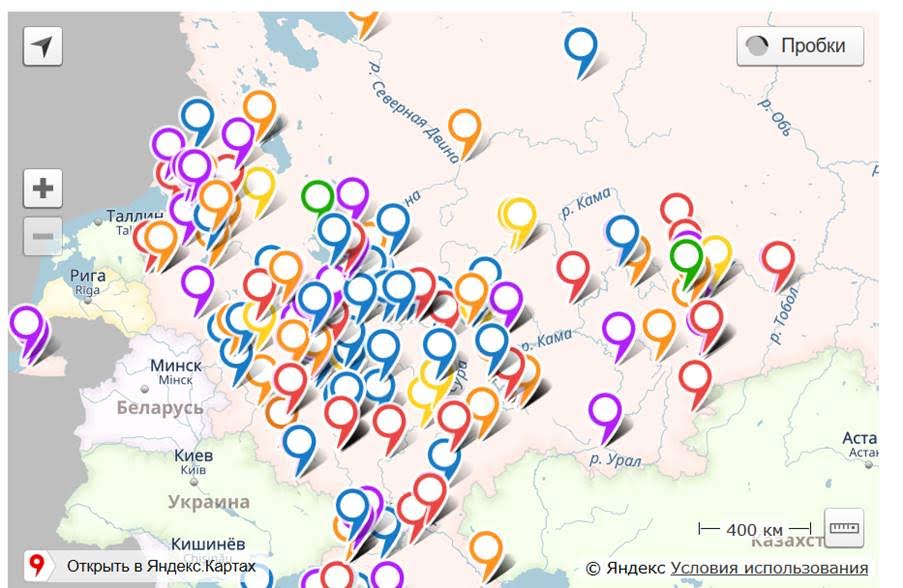

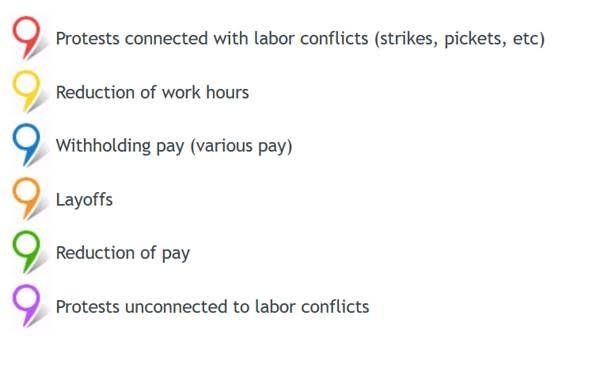

Despite heavy-handed tactics by the government there is a nationwide truck strike in Russia. More than a million truckers have gone on strike across the country. The latest strike started on 28 March 2017 and is continuing despite a showdown on April 15 when even higher charges on the trucking industry took effect. The origins of the protest were the unilateral imposition of a new tax on trucking by the government in 2015. This system (known as the ‘Platon’ system) was introduced to offset what the government said was ‘wear and tear’ on the nation’s road which is so dependent on trucks. The Platon tax applies to all trucks over 12 tons. This is in addition to all the other taxes paid by the truckers. The truckers have resisted paying this tax because they see the revenues earned going, not to repair of the roads, but directly to the pocket of Putin’s closest friend (and judo partner) the billionaire Arkady Rotenberg whose son owns the Platon system.

The current protest was sparked following a government decision to double the Platon fee to over 3 roubles per kilometre ($0.05) starting in mid-April. However, Medvedev was forced to reduce the hike after protests. Drivers argue that the taxes are constraining their incomes and the situation is set to get worse. On April 15, the tax increased from 1.53 roubles per kilometre ($0.027) to 1.91 roubles ($0.033). The government initially planned to increase the rate to 3.06 roubles ($0.05), but has since abandoned the idea. Russia’s transport ministry said the Platon system could gather 23 billion roubles ($406 million) in 2017.

On March 27, the truckers began the rollout of the strike. The police responded with violence and jailing of the leaders. Andrei Bazhutin, chair of the Association of Russian Carriers (OPR) and the duly elected leader of the long-haul truckers opposed to the Plato road tolls payment system, was subject to the harshest crackdown. On March 27, he was put under arrest for 14 days. He spent five of them in a jail before he was released, but during that time the authorities nearly removed his four children from their home and almost caused his pregnant wife to have a miscarriage. On April 5, Rustam Mallamagomedov, leader of the Dagestani truckers, was detained in Moscow.

According to Bazhutin, Dagestan is a particular hotbed of protest. “In Dagestan, 90% of the drivers are private carriers. The republic is small, and so the strike is in everyone’s face. We have strikers spread across the entire country, but Russia is so vast that it’s not so noticeable, although a huge number of people are on strike.” Across Russia the roads are filled with truckers blocking lanes. They are stopping traffic in many of the cities by stopping their trucks in the roads. They have filled all the parking lots with trucks. Despite this there is poor coverage in the state-controlled press and media but it is obvious to anyone in the country who drives. Meanwhile there are shortages of goods and produce across Russia.

There are strikes all over Russia, primarily among workers who haven’t been paid their wages for months at a time. This has been going on for over five years; including doctors, construction workers, teachers, car workers, and factory workers. There was a desperate strike in the pizzeria restaurants who are on a hunger strike in Moscow. It is a good example of the problem, where workers have not been paid for a long period and management refuses to deal with the problem constructively. The workers are desperate because they do not know how to get their hard-earned money. They have been kicked out of rented flats and have no way to pay back their debts, and there is no one and nowhere they can borrow any more money.

Instead of doing everything they can to pay the money they owe their workers, the real employers have been hiding behind “strange” managers, straw men who have been installed as the notional ownership of the restaurants. Practically speaking, there is no one with whom workers can negotiate. The union says it wants to negotiate with the new owners who say that back wages are not their responsibility. In the meantime, strikes continue across Russia.

The inability of the Russian State to fund its internal obligations has become obvious even in Moscow where the medical doctors have been on extended strike (more like a work-to-rule). The Moscow health care reform launched last year shook the city’s medical community to the core. Leaked plans showing that City Hall intended to shut down 28 hospitals in Moscow and the Moscow region, laying off more than 7,000 medical staff, sparked massive street protests by doctors and nurses in November 2014. The strike began on March 24, 2015. It was the first strike in Moscow’s hospitals since the ambulance strike in 1993. It continues largely unresolved.

The inability of the Russian State to fund its internal obligations has become obvious even in Moscow where the medical doctors have been on extended strike (more like a work-to-rule). The Moscow health care reform launched last year shook the city’s medical community to the core. Leaked plans showing that City Hall intended to shut down 28 hospitals in Moscow and the Moscow region, laying off more than 7,000 medical staff, sparked massive street protests by doctors and nurses in November 2014. The strike began on March 24, 2015. It was the first strike in Moscow’s hospitals since the ambulance strike in 1993. It continues largely unresolved.

The traditional solution to labour shortages has always been the employment of migrant labour, but the millions of Kyrgyz, Uzbeks and Tajiks who power Moscow’s huge economy are leaving in droves. There are many migrant workers working in Moscow. They man the construction sites, shovel snow and drive the hordes of “gypsy cabs” that take Muscovites home at night. More than a million of these workers are officially registered in the city, most from the former Soviet Union, and the actual number is likely much higher. In countries like Tajikistan, a major source of labour for Moscow, more than half the GDP is remittances sent home from Russia.

Immigrant life is hard. Wages are low, and workers face discrimination and are poorly integrated into Russian society. Times have recently got more difficult than ever. The rouble has plummeted, and with falling oil prices and western sanctions, Russia is in recession. Added to that are strict new regulations that cut further into migrant labourers’ earnings, leaving workers rethinking their future. “Everyone’s leaving. Wages are small and many places are cutting salaries. Other workplaces are cutting jobs.” Citizens of former Soviet republics (besides the Baltics, Georgia and Turkmenistan) can enter Russia without a visa. But a new system that came into effect on 1 January requires migrant workers to get a “patent,” or work permit, for which they must take a medical exam against contagious diseases, get medical insurance and present Russian ID. They also must pass a test on Russian language, culture and history.

Employers often employ migrant workers under the table, but the new system shifts the onus to pay tax largely on to the workers. A monthly fee – essentially an advance tax – must be paid to keep the permit open. In Moscow, it costs 4,000 roubles a month. For a migrant worker making 20,000 to 25,000 roubles a month, that’s a lot. The permit cost has worsened an already tough situation for migrant workers, who often face discrimination and persecution by crooked employers, officials and landlords. A quick search of rental announcements in Moscow will reveal that most listings are for Russian or “Slavic” people only.

The downtick in workers has put pressure on Moscow’s economy. Industries involving cleaning, selling fast-moving consumer goods and construction are especially reliant on migrant labour. As the population ages, there will be fewer people to work, and few Russians want the kinds of jobs migrants typically do. There’s a contraction of labour resources in general. If you look at immigrants who do construction, finding replacements quickly is hard. Local estimates are that almost 40% of these migrants have gone home.

As these nationwide strikes expand and involve many more people, the independent unions of Russia are gathering their collective strengths to pose a real threat to the existing political system. The police and military may club and beat young protestors and put them in jail or hospital but they can’t club a worker into working anymore; still less a thousand workers. If wages are not being paid by employers or delayed indefinitely, the workers have nothing to lose. They can be militant by doing nothing. Putin hasn’t developed a response to that. Russian independent labour unions pose a real threat to Putin’s control.

Putin may think he can beat and bludgeon the youthful followers of Navalny but it is very unlikely that he can beat down the pressure of an organised work force in the independent unions and the might of the Russian Army. The unions have the ability to shut things down; the military have the weapons and the training.

The Military Threat To The Putin Regime

By far the greatest threat to Putin and his unique system of governance is the growing dissatisfaction in the Russian military with the charade of investments in new equipment and budgets promised by Putin.

One of the most important goads to military dissent is the practice of installing political ‘hangers-on’ into the highest ranks of the service and giving them military ranks. The structure of the Russian military establishment is that it is run by people who have had virtually no contact with actual soldiering. They are politicians; apparatchiki who have worked their way up the political ladder to be entrusted with high military office. They call themselves ‘generals’ but were originally mayors, heads of political parties and hangers-on in the Russian equivalent of Tammany Hall. This is true for many in the highest ranks in the Army. The KGB has always been staffed by people who give themselves military rank by decree. Virtually none of the top leaders had any personal military experience.

The FSB is no different. When the post-war soldiers died out and retired they were replaced by ‘careerists’. The current Minister of Defence, Sergey Kuzhugetovich Shoygu is one of those. Very much like the “Perfumed Princes of the Pentagon” in Washington their backgrounds and tasks are administrative and far removed from war-fighting.

The Russian military has been underfunded since the end of the Warsaw Pact. For years after the end of the USSR and the disappearance of the Warsaw Pact forces the Russian Government failed to provide adequately for the returning soldiers. When the Wall collapsed, the third largest army in the world, the East German, was out of business. Massive quantities of East German (e.g. ex-Russian) military supplies were being offered at cut prices to the world as the re-unifying German state moved to change over to NATO equipment. One of the Soviet Union’s major industries, the arms industry, had the bottom fall out of its market. This was coupled with the enforced withdrawal of Soviet forces stationed in bases across Eastern and Central Europe. The Warsaw Pact disappeared; the COMECON disappeared and there was not enough money in the reserves to keep paying, unilaterally, the costs of keeping Russian troops outside of Russia.

The soldiers were never paid much to begin with but the fall of the Soviet Union meant that they had very little indeed. These soldiers sold, with the connivance of their commanding officers, anything that wasn’t nailed down. They sold it for food and they sold it for trophies that they would carry home as they were demobilised. Most importantly there was no place in the physical Russian military establishment where these troops could be stationed. There were not enough bases inside Russia where the returning troops could be housed. There were no jobs for thousands of trained officers and NCOs. The offset costs for the Soviet Occupation paid by their former ‘satellites’ were no longer forthcoming. There were too many mouths to feed and too few bases in which they could be sheltered.

No one was sure what to do but everyone recognised the danger of a disgruntled army full of people with grievances and with nothing to do. The answer was to keep the numbers down and to keep them poor, weak and demotivated. There was no money or market for new planes and ships; no money for maintenance and very little money for food and shelter.

After the fall of the Soviet Union the military was kept in a state of dereliction and constraint. Russia had suffered greatly as a result of the Afghan War. By the time of Gorbachev’s accession to power the war in Afghanistan had deteriorated badly. Resources were draining from the USSR budget and military progress had stopped and containment was the policy. Gorbachev told the military that they had a year to sort things out. They embarked on a policy of creating an Afghan Army which would notionally take over from Soviet troops, who would then be free to return home. This did not work so, at the end of 1986, they prepared to bring their troops home. The first contingent returned to the USSR from May to August 1988 and the rest from November 1988 to February 1989. It was an expensive and humiliating experience.

After the war ended, the Soviet Union published figures of dead Soviet soldiers: the initial total was 13,836 men, an average of 1,537 men a year. According to updated figures, the Soviet army lost 14,427, the KGB lost 576, with 28 people dead and missing. Material losses included: 118 aircraft; 333 helicopters; 147 tanks; 1,314 IFV/APCs; 433 artillery guns and mortars; 1,138 radio sets and command vehicles; 510 engineering vehicles; 11,369 trucks and petrol tankers. It was a very costly business. Not only was it costly, there was no budget to rebuild the armed forces.

The armed forces had been forced to leave their bases in Eastern Europe to return home. Russia’s most immediate neighbours, those who had been part of the Warsaw Pact, were nervously testing their degrees of freedom from the Soviet embrace. The invasions by Soviet tanks of the East Germans in 1953, the Hungarians in 1956, the Czechs in 1968 and the long history of Polish – Soviet conflict were too recent for these countries to forget.

When Putin came into office he cut the military budget even more. What little remained was devoted to Putin’s new thrust into Chechnya which used up a substantial part of the military budget. Since then Putin has been promising new funds for the military but only small quantities of these funds have arrived. One reason they haven’t arrived is that Russian military prosecutors have found that about 20 per cent of Russian defence spending is stolen by corrupt officers and officials. This should surprise no one as the only way that the officers could maintain their lifestyles was to steal money to do so. They saw what the politicians were stealing so felt little inhibitions.

The anti-corruption campaign in the military has been going on for several years. A large part of the effort is directed at firms that manufacture weapons whose prices to the government are disparate with the market. Last year, this led to a curious confrontation which resulted in Russian shipyards refusing to build submarines for the Russian Navy. The Russian shipyards were in such bad shape that the government tried to buy four Mistral class vessels from France.

On 8 May 2015, the former Defence Ministry official Yevgenia Vasilyeva was sentenced to five years in a penal colony Vasliyeva, who worked as an aide to former Defence Minister Anatoly Serdyukov, was found guilty on eight charges including fraud, money laundering and exceeding and abusing her authority. Four others who worked with her at the state-run Oboronservis holding, where she controlled the sale of Defence Ministry property also received prison sentences, the most severe of which was four years and three months. The group had faced allegations that Oboronservis sold off property cheaply, often to well-connected insiders, depriving the state of 3 billion roubles ($60 million).

Vasilyeva and her accomplices were also convicted of conspiracy to commit the crimes and deceive Serdyukov, who was fired from his post as defence minister in November 2012 and suspected of negligence in using government funds for a private road. Serdyukov was one of President Vladimir Putin’s most loyal courtiers and was granted an amnesty. There have been several other cases in which the politically-connected were let off and the military and defence civil servants were fined or jailed (or both)

Efforts to purge the forces of over 100,000 unneeded (and not very effective) officers ran into stiff resistance. The senior generals and admirals wanted to at least let these men remain until they reach retirement age, and leave with dignity, rather than being, in effect, fired.

Most of the submarine fleet is scrap and unusable. Tanks are no better. Except for the new Armata Tank, only a very few of which have been produced, the most modern tank Russia has is the T-90, which entered service in the early 1990s. Most of the 20,000 tanks (72 per cent of them in storage) in the Russian army are T-72s and T-80s. Russia planned to replace most of those T-72s and T-80s with T-90s and a new design, the T-95, by 2025 but the money ran out. On March 25, 2012 Major-General Alexander Shevchenko announced the massive scrapping of Russia’s tanks, APC and trucks, including T-80, T-64, T-55, tanks as well as a number of army trucks. Similar schemes were scheduled for the Russian air force.

The problems of supply are not just quantitative; the biggest problem is quality. Arms manufacturers are in no position to use the funds even if they get them. Take, for example, Uralvagonzavod, the country’s only tank manufacturer. Putin himself bowed to pressure to place an order for 2,300 tanks to be built over the next 10 years despite a statement by General Staff head Nikolai Makarov that the military would not be purchasing any tanks in the next five years due to their substandard quality. In an article in RIA Novosti on 15 March 2012, Ground Forces Chief Col. Gen. Alexander Postnikov said that the most advanced weapon systems manufactured for Russia’s ground forces are below NATO and even Chinese standards and are expensive; “The weapon models that are manufactured by our industry, including armour, artillery and small arms and light weapons, fail to meet the standards that exist in NATO and even China,” He said that Russia’s most advanced tank (at that time), the T-90, is in fact a modification of the Soviet-era T-72 tank [entered production in 1971] but costs 118 million rubbles (over $4 million) per unit. “It would be easier for us to buy three Leopards [Germany’s main battle tanks] with this money,” Postnikov said.

More importantly, it has invested very little in military R&D or at least an R&D with a workable product. The industry has faltered from lack of funding, a lack of R&D and the disappearance of a substantial portion of its skilled labour force. An overwhelming fraction of the defence workforce drifted away some time ago, in search of better career opportunities, and those who remain are generally older workers contemplating retirement. Increasingly elderly design and production facilities are suited for legacy weapons, rather than world standard designs. The emerging Russian Rust Belt cannot sustain a world class machine tool industry, which would be the foundation on which a Russian arms industry might be revived.

Ironically the most developed facilities for military production were in the Ukraine. The military-industrial complex of Ukraine is the most advanced and developed branch of the state’s sector of economy. It includes about 85 scientific organizations which are specialized in the development of armaments and military equipment for different usage. The air and space complex consists of 18 design bureaus and 64 enterprises. In order to design and build ships and armaments for the Ukrainian Navy, 15 research and development institutes, 40 design bureaus and 67 plants have been brought together. This complex is tasked to design heavy cruisers, build missile cruisers and big antisubmarine warfare (ASW) cruisers, and develop small ASW ships. Rocketry and missilery equipment, rockets, missiles, projectiles, and other munitions are designed and made at 6 design bureaus and 28 plants.

Ukraine has certain scientific, technical and industrial basis for the indigenous research, development and production of small arms. A number of scientific-industrial corporations have started R&D and production of small arms. The armour equipment is designed and manufactured at 3 design bureaus and 27 plants. The scientific and industrial potential of Ukraine makes it possible to create and produce modern technical means of military communications and automated control systems at 2 scientific-research institutes and 13 plants. A total of 2 scientific-research institutes and 53 plants produce power supply batteries; 3 scientific-research institutes and 6 plants manufacture intelligence and radio-electronic warfare equipment; 4 design bureaus and 27 plants make engineer equipment and materiel.

Perhaps the best example is the company Motor Sich. It has been the sole producer of engines for the MI-8 and MI-24 helicopters. It produces these engines for the Russian helicopter industry and a wide range of other military components. The air firm Antonov is based in the Ukraine and is one of the major suppliers of aircraft for the Russian Air Force and for Russian arms exports.

The ability of the Russian industry to fill its own needs is compounded by the fact that it needs Ukrainian parts and subassemblies for its exports. Losing control of the Eastern Ukraine has jeopardised Moscow’s ability to fulfil multibillion-dollar international contracts without Ukrainian inputs. It also supplies the engines for the jointly-produced AN-148 planes. Ukraine and Russia had plans to produce 150 planes of this type worth $4.5 billion. Other exporters to Russia include Mykolayiv-based Zorya-Mashproekt, which sells several types of turbines to Russia, including those installed on military ships. Another is Kharkiv-based Hartron, which supplies the control systems for Russian missiles.

The Yuzhmash plant in Dnipropetrovsk was the only service provider for Satan missiles that Russia uses. The Ukrainians are also the main supplier of spare parts which its armed forces desperately need. Russia is scrambling to supply domestic factories with the technology needed to produce these components inside Russia. However, much of the higher inputs of technology, especially in the electromechanical area, are sourced in France, Germany, Britain and the U.S.; now effectively closed off to Russia by sanctions. Despite efforts by the Russian troops in the Eastern Ukraine many of the existing plants were attacked and damaged by the rebels of Donetsk and Lugansk. Additionally, the skill set of the Russian factories has been degraded by the demographic crisis of Russia and the ageing population. Now Ukraine has re-engineered its military and analogous plants to provide weapons, aircraft and electronic systems to the West.

One of the biggest problem for the Russian military, however, is manpower. A problem in relying on conscript soldiers is their term of service. At the beginning of 2014 the services were only 82% manned – a shortage of nearly 200,00 personnel. This was exacerbated by the reduction in 2013 of the term of conscription to one year of service as opposed to the previous three years. Since these terms of service are so short, military adventures have to be timed with the availability of soldiers in their cycle of enlistment. More importantly these conscripts are untrained which has meant that they do not have the experience or training to fill the important jobs of operating and maintaining the sophisticated weapons systems used by the special forces units like the Air Assault Troops (VDV) and other elite forces. There is a deep deficit in Russian Reserve units which are used to carry out the training of conscripts despite the establishment of a new Reserve Command in 2013. There has been a reduction in the numbers of conscripts successfully evading the draft; a frequent Russian problem.

However, there is another manpower problem which is even more difficult to handle. Putin has been firing large numbers of the Russian military leadership. On the 29th of June 2016 Putin’s Ministry of Defence suddenly announced it was firing 50 naval officers, including Vice Admiral Viktor Kravchuk and chief of staff Rear Admiral Sergei Popov. They were both fired for ‘cause’, as were several other unnamed senior officials from their posts in the Baltic Fleet. This came as a great shock to the country as such a purge of serving top commanders had not been seen since the days of Stalin, during the Yezhovshchina of 1936-38. Earlier, Admiral Viktor Chirkov had been removed in November 2015 officially because of ‘health concerns’. Chirkov, who had been Kravchuk’s patron in the navy for many years, was rumoured to have also been removed due to complaints about inadequate readiness in some units.

In late 2014 there had been a smaller purge of the Russian military when Putin dismissed twenty generals from their posts. In February 2014 Putin had dismissed six other generals. These generals were dismissed by a presidential decree announced through the Gazette and without fanfare. The officers dismissed included the lieutenant general of police, Sergey Lavrov, as well as the head of media relations in the Ministry of Internal Affairs, Andrei Pilipchuk. Another was the first deputy commander of the central regional military command, Vladimir Padalko. Some other lower-rank officers were dismissed as well at the time.

The top Russian military leadership has not bene afraid of complaining about Putin and the political interference in the military, despite the exaggerated promises of an expanded budget, new equipment, and the modernisation of the Russian military might; very little of which the economy can afford. It soon became apparent to the military that they had been sold a kukla (in Russian slang kukla is a roll of paper with large denomination bills on the outside to suggest a wad of real money. Inside this roll of bills is only scrap paper).

Even more importantly the Russian military has a history of defiance of political controls when it has become a clash of principles. They said it was wrong to use Russian troops against Russian people. The Russian military did not want to fight the war in Chechnya under Yeltsin, Gorbachev and Putin. Yeltsin’s adviser on nationality affairs, Emil Pain, and Russia’s Deputy Minister of Defence, Boris Gromov, both resigned in protest at the invasion, as did Gen. Boris Poliakov. More than 800 professional soldiers and officers refused to take part in the operation; of these, 83 were convicted by military courts and the rest were discharged. Later Gen. Lev Rokhlin also refused to be decorated as a Hero of Russia for his part in the war. This is why, under Yeltsin, the war in Chechnya was fought almost entirely by the military forces of the MVD (Ministry of the Interior) not the Army.

This is important in today’s battles in that the conflict between the Russian Army and the MVD has become institutionalised. In April 2016 President Putin announced the creation of the National Guard, (‘Rosgvardia’) a powerful structure that includes more than 180,000 interior ministry troops plus special police units. Putin’s shakeup creates a military and police force of up to 400,000 well-trained servicemen loyal to him personally. The newly appointed commander is one of Putin’s most trusted men, a former undercover KGB agent named Victor Zolotov. Putin has created a vast Praetorian guard, loyal only to him. He has announced that the Rosgvardia is superior to the military and its needs take precedence over any military body; indeed, it can investigate and prosecute the military without judicial review.

The only comparison to the role of the Rosgvardia is the introduction of the Oprichnina by Tsar Ivan the Terrible in Russia between 1565 and 1572; a policy of secret police, mass repressions, public executions, and confiscation of lands. There was terror in the land at the presence of the Oprichniki (see the opera of that name by Tchaikovsky). There is no guarantee that the Russian military will demonstrate the same fear and every chance that they will continue their policy of opposing the MVD and Praetorian Guards.

So, Putin may think he can beat and bludgeon the youthful followers of Navalny but it is very unlikely that he can beat down the pressure of an organised work force in the independent unions and the might of the Russian Army. The unions have the ability to shut things down; the military have the weapons and the training.

Dr. Gary K. Busch, for Lima Charlie News

Dr. Busch has had a varied career-as an international trades unionist, an academic, a businessman and a political intelligence consultant. He was a professor and Head of Department at the University of Hawaii and has been a visiting professor at several universities. He was the head of research in international affairs for a major U.S. trade union and Assistant General Secretary of an international union federation. His articles have appeared in the Economist Intelligence Unit, Wall Street Journal, WPROST, Pravda and several other news journals. He is the editor and publisher of the web-based news journal of international relations www.ocnus.net.

Lima Charlie provides global news, insight & analysis by military veterans and service members Worldwide.

For up-to-date news, please follow us on twitter at @LimaCharlieNews

In case you missed it: