Inside the biosafety level 4 lab at the National Emerging Infectious Diseases Laboratories (NEIDL) in Boston, researchers wear three sets of gloves and breathe air piped into moon suits through snaking tubes. Before them, under a plastic shield, are human lung-sac cells grown from organoids, blobs of cells that mimic organs.

Now it’s time to infect them with the coronavirus.

What happens next could shed light on the strange and deadly effects of covid-19—because it’s not just the virus that matters, but the body’s reaction to it. People are dying from that reaction, and organoids could help zero in on where the damage is worst. Accurate cell models are already pinpointing how the virus gets into the body, where it causes the most harm, and will help in the search for treatments.

Many virologists work with computer data, or with surrogate viruses into which they plug parts of the covid-19 germ, or sometimes by infecting supplies of monkey cells that viruses like to grow in. But these surrogates can’t tell you what the actual virus does to specific human cell types. “If you work with the real thing, you get real results,” says Elke Mühlberger, a microbiologist at NEIDL, which is operated by Boston University. “If you are interested in the host response, then substitutes are of no use.”

NEIDL

One area where research on lab-made human lung tissue could pay off is in testing covid-19 drugs. Before trying any potential antiviral drug on people, researchers test their potency at blocking the virus in the lab. But after years of adaptation to a petri dish, standard laboratory cells are far from normal. “They’ve lost their ability to act as lung or liver, they don’t respond to interferon—they are very different than the real thing,” Mühlberger says. “They don’t do much other than get infected.”

Cells from organoids are different.

Tiny organs

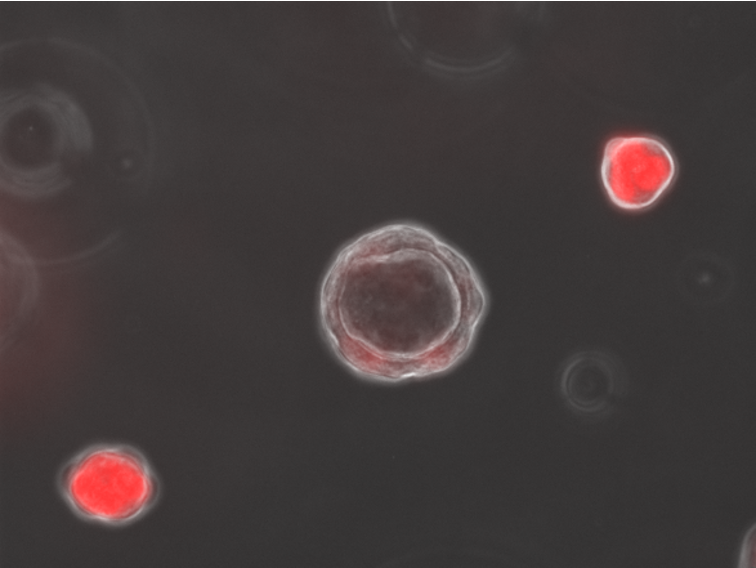

Organoids are complex mini-tissues created from stem cells. These master cells are allowed to multiply and self-organize until they end up creating tiny clumps that can have the basic cellular makeup—and functions—of a real organ. There are mini-guts with delicate wrinkles, brain blobs that emit EEG waves, and structures that look surprisingly like real embryos.

Organoids had their debut as a virus-solver during the Zika outbreak, when infecting tiny lab brains showed that the virus had a preference for young, developing neurons. That offered an explanation for why the mosquito-borne germ was causing a birth defect, microcephaly, in some Brazilian newborns.

Organoids may also help researchers study animal viruses they haven’t had a good look at yet because they have proved difficult to grow in a laboratory setting. In May, scientists in Hong Kong cultivated mini-guts from horseshoe bats, the very species eyed as the root of the covid-19 outbreak, which harbor thousands of viruses about which we yet know little.

Lung cells

The research in Boston uses lung tissues being created at several area laboratories, including some that match parts of the alveoli, the puffy air sacs that exchange oxygen in the lung and that get overwhelmed in severe cases of covid-19.

Finn Hawkins, who runs one of the organoid labs, is a lung doctor who just finished a stint in an ICU caring for covid-19 patients. “I have never seen anything like it,” he says. “To me, the striking thing is the degree to which it causes severe lung damage in some patients. It’s not like Ebola, where everyone gets sick.”

The serious cases struggle with the same mysterious symptoms. Patients on ventilators are supposed to get weaned off. Instead, some are seized by a “cytokine storm,” an out-of-control inflammatory response, matched with a fever that won’t break. What’s killing most covid-19 patients is they come to the point where they can’t breathe at all. “Their markers go up; they need oxygen. The sudden worsening—that is something I have never seen before and now see over and over again,” says Hawkins. “You start to wonder what is going on, what’s driving the worsening.”

Hawkins says supplies of specific airway and lung cells could answer two questions: first, which cells let the virus into the body, and second, which are key to the devastating effects. Combine stem-cell-derived lung cells with the ability to sequence and track molecules inside individual cells and the result is “unbelievable resolution,” he says. “You can get information that is otherwise impossible to get.”