Ryan met his Israeli girlfriend while on an extended stay in the country following a Birthright trip. The 27-year-old fell in love and decided to make Israel his home. When he approached Nefesh B’Nefesh for help with his job search last August, Ryan claims, the non-profit organization mostly offered him binary options, forex and other call center sales jobs.

Ryan eventually landed a job with a high-tech e-commerce site that sold products to the US market. But it wasn’t the honest, satisfying work he had hoped for. Using superior search engine optimization (SEO), the company managed to place at the top of most Google searches for its category. The product, though, was shoddy, and Ryan’s job was to field the hundreds of daily customer complaints and to ensure that customers got an exchange, but rarely a refund. Ryan was told to lie to customers and say he was in New York, even going so far as to complain about the cold when it was a perfectly balmy day in Tel Aviv. His bathroom breaks were timed, and his bosses were mean and abusive, he related.

“It wasn’t as skeezy as binary options or forex,” he said, “but it was pretty skeezy.”

When Nicole, a fashion designer in her 20s, moved to Israel from France, she soon landed a job in the fashion industry. The problem was that the salary barely covered her Tel Aviv rent, let alone food and transportation. So she took a job with an online gambling site. She started out in customer support, but eventually the unregulated company asked her to begin cold calling clients and persuading them to gamble away their savings.

“If someone told you he had savings to send his children to college, you were supposed to persuade him to deposit it in the casino, tell him he can win even more money. Unfortunately, there are people who will fall for that.”

Nicole refused and quit, and the company was eventually shut down following an FBI investigation.

The experience still haunts her. “I feel it was not good for my soul.”

The wages of desperation?

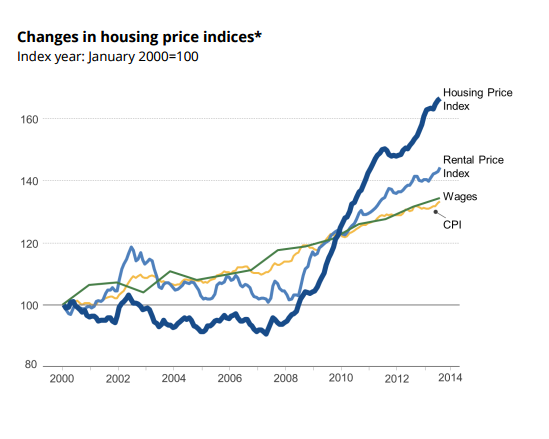

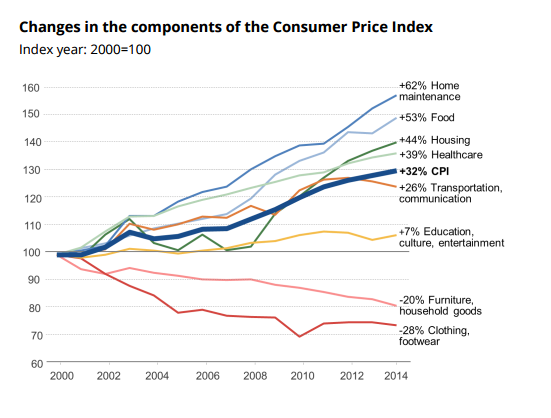

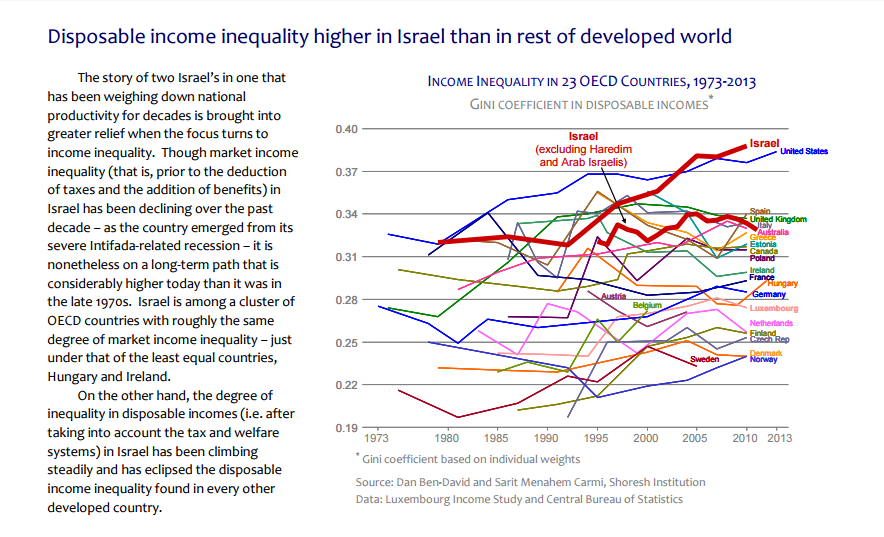

But in a country where one out of every five Israelis lives below the poverty line, according to the Taub Center’s 2016 Picture of the Nation Report, where disposable income inequality is the highest in the developed world, where the cost of living relative to salaries is higher than in every OECD country except Japan, and where housing prices have skyrocketed in the last eight years, there are a lot of economically desperate people.

Courtesy of the Taub Center

Combine this market of desperate job seekers with the accelerated growth, over the last 5-10 years, of a shadow high-tech industry comprising forex and binary options, online gambling, porn, fraudulent companies with high SEO rankings, and the affiliate marketing, adtech and payment companies that service these shady industries, and you have a perfect storm of good people who find themselves, perhaps unwittingly and unintentionally, asked to do evil things.

When asked to estimate the size of Israel’s shady and fraudulent high-tech sector, one industry researcher told The Times of Israel that perhaps 10 percent of high-tech companies fall into these categories, but because such companies are highly profitable, they may account for some 30% of the high-tech industry’s revenue.

So what can be done? In a global survey, the Gallup organization found that more than safety, peace, freedom or love, respondents the world over prize a good job, meaning a steady job with a paycheck and 30 or more hours of work per week.

How can Israel provide more good jobs for its citizens — jobs that are honest and make a positive contribution? If and when Israel’s binary options and other scam industries are shut down, who will absorb its thousands of former employees, at least those whose crimes do not land them in jail?

The Times of Israel asked three economists what are the deep changes that need to take place in the Israeli economy so that the country can offer good jobs to all its citizens in decades to come.

High tech is not the only answer

It’s no news flash that high-tech offers the best salaries in Israel’s private sector, salaries that are competitive at an international level, with some programmers bringing home payslips of 35,000 shekels ($9,000) a month. The problem, say Eitan Regev and Gilad Brand, economists at the Taub Center for Social Policy Studies in Israel, is that high-tech jobs account for only 10-15% of positions in the private sector, while most jobs that aren’t high tech suffer from low productivity and salaries well below their OECD counterparts.

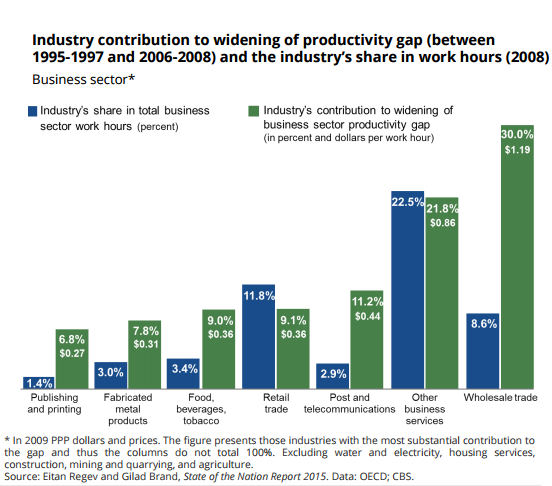

(Courtesy of the Taub Center)

Brand says that unlike in Japan, where the rising tide of the economy’s growth lifted all job seekers, in Israel 85% of wage earners have been left behind.

“Israel’s relative advantage is in an area that is so narrow that its success doesn’t increase salaries for other sectors,” says Brand. “We have to diversify the sources of our exports, which is the only engine of perpetual increases in salary and productivity.”

Brand says that the Israeli government’s policy, since the 1990s, to subsidize and incentivize the high-tech sector has paradoxically hurt the rest of the economy.

“High-tech companies export a lot and the shekel gets stronger. But that makes it less worthwhile for companies that aren’t high tech to export,” explains Brand. “Small businesses and weaker businesses can’t compete globally, and that’s why the job market is the way it is.”

Brand says the answer is to integrate high tech into traditional sectors like textiles or heavy industry, making it possible for Israel to compete with the Far East. He cites Israeli undergarment company Delta Galil as a success story in this respect. Realizing that Israel’s comparative advantage lay in technology, Delta Galil started manufacturing perspiration-wicking, body contouring and seamless clothing, and has become a major supplier to brands such as Calvin Klein, Nike and Victoria’s Secret.

“Integrating technology is the only way to survive; the same could happen in the food industry,” he says. “With more good jobs, there would be more competition for workers and salaries would go up in the entire economy.”

Stef Wertheimer, founder of the Israeli tooling firm ISCAR, is a big proponent of the need to build more manufacturing to ensure a good life for future generations Israelis, notes Brand.

Rent-seeking middlemen

Some industries are a bigger drag on productivity than others, say Regev and Brand, singling out wholesalers as a group and the food industry in particular as the worst offenders.

“The wholesale industry is very problematic,” says Brand. “It causes high prices and low productivity. Many engage in rent-seeking behavior (exploiting monopoly status to extract money without providing a commensurate benefit).

“They will come to a farmer and say, ‘You don’t want to sell your tomatoes for 1 shekel? Ok, let’s wait a day and watch it rot in the field.’”

(Courtesy of the Taub Center)

Brand says that productivity among Israeli wholesalers has not risen in 15 years, while in the OECD it increased by $10 per hour.

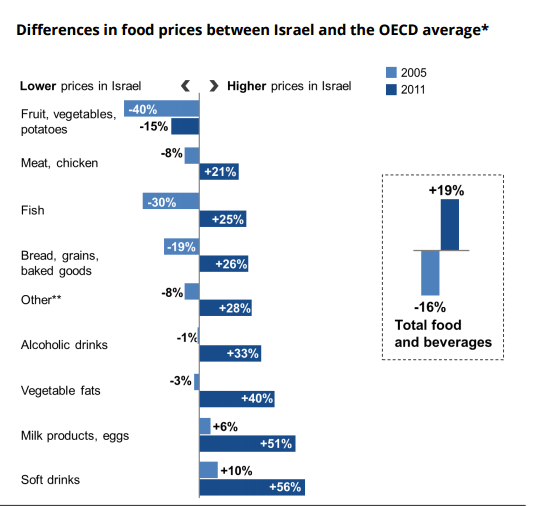

Meanwhile, in 2005 food prices in Israel were 16% below the OECD average, now they’re 19% higher. Brand cites the sale of Tnuva to Apax, the Remedia tragedy, and the subsequent slowdown of imports, as well as the purchase by supermarket chain Shufersal of its competitor ClubMarket in 2006, as the immediate causes.

(Courtesy of the Taub Center)

As for the solutions? Increasing food imports as well as initiatives by farmers to sell their produce directly to consumers through the Internet are a start, says Brand.

‘The poor are us’

Ask Dan Ben-David, president of the Shoresh Institution for Socioeconomic Research, how to create more good jobs in the Israeli economy and he will tell you that it all comes down to government investment in public infrastructure — health care, transportation and, most importantly, education.

“We have some of the best universities in the world in Israel,” Ben-David says, “in terms of the quality of research and students. But they are not representative of the entire country.”

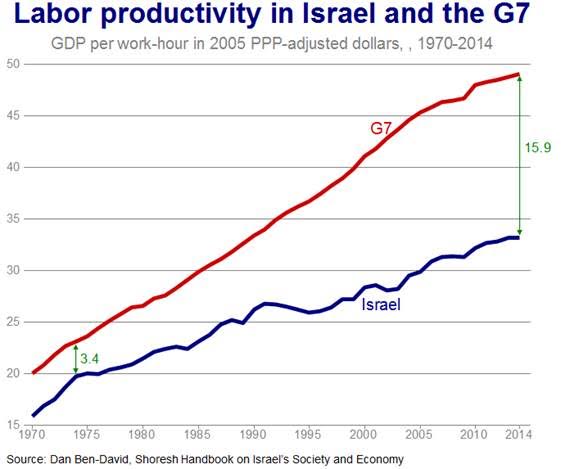

Ben-David says that the amount produced per hour in Israel is the lowest in the developed world and this is attributable to the fact that “a large segment of the population receives a third-world education.”

“I may be the best engineer in the world, but if I work with a bunch of people who don’t know English, for instance, or don’t know math, I will end up doing the work for them. It brings down their productivity but it brings down mine too.”

Ben-David says that Israel is actually two nations in one, the cutting-edge Start-up Nation and those disadvantaged groups, specifically Haredim, Israeli Arabs and poorer people in the periphery, who lack the skills to contribute to a modern economy. This gap, he says, is causing Israel to fall further and further behind the world’s leading countries in productivity.

Ben-David says this is not about helping the poor.

“The poor are us! If we don’t allow them to reach a point where they can be self-sufficient, then the entire burden of the country will rest on the shoulders of the few who are getting a good education. But we need everyone else. Try fighting a war with only a few of your neighbors.”

Where did the money go?

Ben-David paints a frightening picture of how successive Israeli governments shifted priorities away from education and investing in human capital, starting in the 1970s.

“Until the mid-1970s we built universities, but not one research university has been built since, even though the population has more than doubled. There are fewer researchers in Israel today than 40 years ago and one-fifth less faculty members today than 40 years ago.”

Ben-David says that in the early days of the state, Israel invested money building towns, roads, universities and hospitals, but even though the country is much wealthier today, the money has been diverted elsewhere.

(Courtesy of the Shoresh Institution)

“For instance, the number of hospital beds per capita grew steadily until the late 1970s. But today we have one of the lowest shares of hospital beds in the developed world. You can get a first-world doctor here, but you will be hospitalized in third-world conditions, in the corridor or the lunchroom. That’s how people get infections.”

Asked where the money is being diverted, Ben-David says it is hard to say, since Israel’s budget is not transparent.

‘You can get a first-world doctor here, but you will be hospitalized in third-world conditions, in the corridor or the lunchroom’

“On the one hand you have a very detailed budget — you have thousands of budget items — but you can’t sort them because what’s written on the budget item is undecipherable in many cases.”

Nevertheless, Ben-David believes that special interest groups, including Haredim and crony capitalists, are getting a large share of money that should be going to the population as a whole.

The solution, he says, is to create a government of the center. If the Likud, Kulanu, Yesh Atid and the Zionist Union formed a coalition, it would contain two-thirds of Knesset members and could begin to tackle the core issues that are crucial to Israel’s future — like overhauling the education system.

“In 20 years, those parties will represent barely half of the population. What is very difficult today will be impossible to do in a few decades. But we don’t pressure the parties we vote for to cooperate with each other.”

A cautionary tale

Ben-David says that he, like many of his colleagues at Tel Aviv University, has a PhD from one of the world’s leading universities (University of Chicago) and could have made a career anywhere in the world.

“We didn’t have to come back, but we came back because this is where we want to live. This is our home.”

‘If you have the wrong policies, a country can fall apart. Countries end’

Nevertheless, if this generation doesn’t get things right, their children may no longer want to live here.

“Look at Lebanon. A few decades ago Beirut was called the Paris of the Middle East. There was a certain balance between the more educated and the less educated people. The Christians were primarily educated and the Muslims were not. The Christians lost, and the Lebanon that was a semi-democracy is gone. Look at the Soviet Union. If you have the wrong policies, a country can fall apart. Countries end.”

As for Israel, he adds, “this country has a lot going for it, but we need to get it right. If we don’t take care of all of the country’s children, our children will choose not to remain here.”

Ryan, the recent immigrant, also hopes the country gets it right. He quit his call center job and is now working in construction.

“I like it here and have no plans to leave,” he said. “I knew it would be hard to make a living in Israel. I just didn’t know it would be this hard.”