The California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) took effect last Wednesday on January 1. And while I received numerous “our privacy policy has changed” emails, it was very challenging to find websites with actual “Do Not Sell My Personal Information” buttons or links.

I finally started seeing them at the end of last week. However, the notices were often very inconspicuous, perhaps as a test of minimum compliance. Indeed, it appears many publishers are trying to call as little attention as possible to the data opt-out option for consumers.

Not making it easy for users to find the opt-out entry point

If you’re not actively looking, you won’t find them

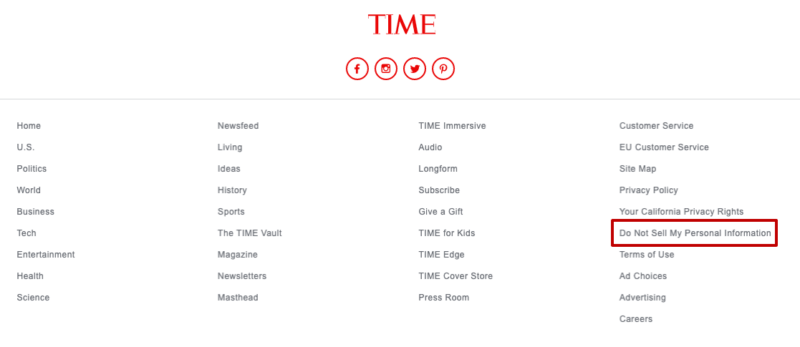

A fairly representative example comes from Time’s homepage. The “Do Not Sell” link is sixth on the list, in the far right column at the very bottom of the homepage. This is not something that would be casually discovered by most site visitors; there’s lots and lots of scrolling required.

It was the essentially same for Pandora, Hulu, The NY Times, WSJ.com and many others. The required links are at the very bottom of their respective homepages, in small fonts.

Netflix hides its opt-out language behind a plain-vanilla “privacy” link on its homepage. The same is true for Amazon. CCPA links are also very difficult to find on both Google and Facebook. Those not actively looking for them won’t find them.

‘Do Not Sell’ links in very small fonts

A user-friendly example — sort of

Conde Nast publications were more user friendly. On Wired, for example, a pop-up notification asks you accept an updated privacy policy; and shortly thereafter a “cookie banner” appears with a relatively conspicuous “Do Not Sell” button at the bottom of the page (see below).

In my unscientific survey of sites I frequent, Conde Nast’s treatment of “Do Not Sell” was the most consistent with the language of the statute, compared with what I would call “grudging” compliance by most of the other publishers, which appear to have consciously buried the links.

There’s no “opt-out” option at all for Amazon, Google and Facebook, which instead point to other mechanisms to control user privacy. Generally, they’re also taking the position that they’re not “selling” personal data. There’s a good deal still to be clarified — and there’s a longer discussion involving Google, Facebook and Amazon — but retargeting is clearly implicated by CCPA.

Conde Nast more ‘clear and conspicuous’

What does ‘clear and conspicuous’ mean exactly?

The statute itself requires publishers to “Provide a clear and conspicuous link on the business’s Internet homepage, titled ‘Do Not Sell My Personal Information,’ to an Internet Web page that enables a consumer, or a person authorized by the consumer, to opt-out of the sale of the consumer’s personal information.”

We can debate the meaning of the phrase “clear and conspicuous” but what most of these publishers are doing, save Conde Nast and a couple of others I found, probably doesn’t qualify. They’re playing hide the ball.

Page 2: dense text and fine print

Lots of exhausting fine print

For those intrepid users who locate the links and click through, the pages that follow are often replete with fine print and complexity. Even Conde Nast, on the better end of the spectrum, presents the above potentially confusing screens. (The highlighting is mine.)

After you “confirm my choices,” you’re taken to a form and required to (wait for it) . . . provide a bunch of personal information. You then receive an email and are required to offer a second confirmation of your choice. All of this takes you away from the article you originally wanted to read.

Different publishers and their software vendors offer somewhat different treatments and user experiences. But there’s frequently lots of dense text and legalese, all of which is going to be exhausting for the average user to contend with. As I’ve argued before, users just seeking read an article are not going to want to take five minutes, at a minimum, to do all of this.

Multiply that by 10 or 20 or 50 sites in a day or week and most users will just carry on as usual for convenience and to avoid “privacy fatigue” — that is if they looked for the “Do Not Sell” links in the first place. Most publishers are probably hoping users either won’t notice or simply give up.

Personal information required to prevent a transfer of personal information

Educate, don’t ‘comply’

These initial efforts to comply with CCPA may uphold the letter but not the spirit of the law. Hiding links at the bottom of the page doesn’t inspire consumer trust or bring more transparency to users. While the path forward is complex and still murky, smart marketers are embracing privacy and not fighting it.

As a practical matter, I also believe these “bottom of the homepage” placements won’t been deemed sufficiently conspicuous and publishers will be compelled to make them more prominent, as well as potentially simplify the entire process. Rather than hoping users won’t notice, publishers and technology providers should be educating them about the benefits of not opting-out — in language that non-lawyers can understand.