Commitment bias is the desire and tendency to be consistent with what we have done or said before.

But why do people do this?

Robert

Cialdini, Professor Emeritus of Psychology at Arizona State University, says:

“People

want to be congruent with what they have committed to in the past, especially

if that commitment is public…. Once we have made a choice or taken a stand, we will encounter personal

and interpersonal pressures to behave consistently with that commitment.”

Making a

public commitment intensifies our intentions, as does writing a commitment

down.

Commitment Bias Illustrated

To reduce

non-attendance by patients at a GP surgery in Bedfordshire, UK, patients were

asked to write down the details of their appointment. This reduced

non-attendance by 18% compared to a reduction of only 3.5% for patients who had

verbally committed to attending.

Another example comes from a

trial run by the Behavioural Insights Team (BIT) in 12 jobcentres in Essex in

2013. People signing-up to receive benefits are encouraged to get back into

work again as quickly as possible, and to receive benefits must demonstrate

they’re actively looking for work; applying for 3 or more jobs in the 14 days

between each appointment at the centre. The usual procedure was to retrospectively

sign to say they had been actively looking for work to receive their next

set of benefits. The BIT flipped this process. Now jobseekers had to commit to

search for work in the coming 14 days. This included making a detailed plan for

what they planned to do for their job search on which day, fitting it around

their everyday routines.

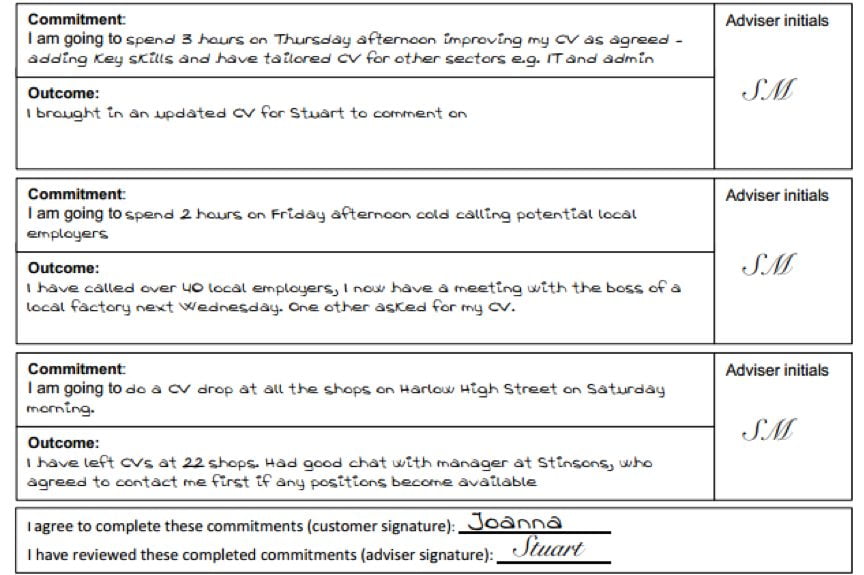

The image below shows such a plan. This was a publicly written commitment made in the presence of jobseeker’s advisor. Both factors strengthen the commitment effect. Jobcentres also redesigned the first interview and ran resilience building exercises for all jobseekers. After 3 months, the commitment strategy and additional changes helped jobseekers get back into work more quickly.[1]

Another area in which commitment

bias is applicable is encouraging everyday environmentally friendly behaviour.

For instance, prompting hotel guests into being more environmentally friendly

by reusing towels, turning off the lights and not wasting water. Additionally

to valuable environmental benefits, towel reuse and turning off lights also

reduces hotel running costs. Estimates suggest that reusing towels and linens

saves a hotel $6.50 per room per night, amounting to annual savings of around

$460,000 for an average size hotel.

Amongst the guests it’s largely lack of routine, forgetfulness and low

salience of hotel requests that stops environmentally considerate behaviour,

rather than deliberate wastage.

In 2010, Disney Research wanted

to see if they could nudge guests into changing their ways in the Disneyland

hotel, Anaheim, California. They tested the impact of leveraging commitment

bias on hotel guests. Specifically, at check-in, they asked guests to pledge

and commit to reusing their towels each day during their stay. Guests were also

given a ‘Friends of the Earth’ pin to wear after pledging. They tested their

intervention over several weeks, during which time over 2,000 guests took part.

The impact? Guests were 25% more

likely to reuse their towels when they had pledged to do so and had received a

‘Friends of the Earth’ pin. They also hung up over 40% more used towels

compared to a control group.

The researchers estimated that

the impact of the pledge and pin combined would save the hotel washing 147,000

towels a year (that’s 2,500 loads of laundry), saving 700,000 gallons of water

and $51,000 per year.

The researchers also measured if

any spillover effects from guests committing to reuse their towels, such as

their being more likely to turn off the lights existed. It did indeed have an

effect – pledging to reuse towels and wearing a pin meant that there was approximately

70% chance that guests would turn off the lights, compared to only a 50% chance

among guests in the control group.

So, what does all this mean?

For market researchers, building commitment may help improve participant retention. For example, on online forums participants might be asked to type ‘I’m ready!’ to do a task rather than tick a box to say they have ‘read the instructions’. We might also remind people of prior commitments in order to encourage participation. If people have ticked a box to say they are happy to be re-contacted – we might remind them of this, stating that ‘we want to speak to you because you said you would be happy to speak/were interested in…’

NEXT IN THE

SERIES: Every three weeks The Behavioural Architects will put

another cognitive bias or behavioural economics concept under the spotlight.

Our next article features the concept of Paradox of choice.

www.thebearchitects.com

@thebearchitects

PREVIOUS ARTICLES IN THE SERIES:

System 1 & 2

Heuristics

Optimism bias

Availability bias

Inattentional blindness

Change blindness

Anchoring

Confirmation Bias

Framing

Loss aversion

Reciprocity

Hot cold empathy gaps

Social norms part 1

Social norms part 2

[1] Sanders, M., Briscese, G., Gallagher, R., Gyani, A., Hanes, S., Kirkman, E., & Service, O. (n.d.). Behavioural insight and the labour market: Evidence from a pilot study and a large stepped-wedge controlled trial. Journal of Public Policy, 1-24. doi:10.1017/S0143814X19000242