A federal judge on Thursday rejected Jeff Bezos’ latest legal attempt to overturn NASA’s multibillion-dollar moon lander contract with Elon Musk’s SpaceX. The decision ended a monthslong battle between the space companies of two of the world’s richest men that posed a significant obstacle to NASA’s plans for returning humans to the moon for the first time since 1972.

The ruling makes it all but certain that whenever American astronauts return to the lunar surface, they will be traveling in a spacecraft built by Mr. Musk’s company. That adds another victory for SpaceX, a company that has become a dominant player in orbital spaceflight, including serving as a primary partner of NASA in carrying astronauts and cargo to the International Space Station.

But NASA has been unable to work on the program with SpaceX for the duration of Blue Origin’s legal challenges, which may delay the return to the moon.

“It’s been disappointing to not be able to make progress,” said Pam Melroy, NASA’s deputy administrator, in an interview on Wednesday before the ruling was released. She added that meeting with the company to assess the timeline for the moon mission was a “very high priority” for NASA, now that the litigation ended in its favor.

Blue Origin sued NASA in August, contending that the agency unfairly awarded to SpaceX a $2.9 billion contract in April to conduct the first two missions to the moon. The contract feud was one of many industry conflicts that reflected the clashing ambitions of two entrepreneurs who are pouring billions of dollars into rival efforts to normalize space transportation.

The launches that were the subject of the dispute are to be part of Artemis, NASA’s flagship effort to build an American presence on the lunar surface. The coveted contract to put humans on the moon would have provided a crucial boost to the credibility of Blue Origin, which has flown humans to the edge of space in a tourist spacecraft, but has struggled to advance its ambitions of building a rocket that could lift cargo to orbit for NASA and the Department of Defense. After it lost to SpaceX, Mr. Bezos’ company engaged in months of legal jostling, rigorous lobbying and public complaining.

The ruling by Judge Richard A. Hertling of the U.S. Court of Federal Claims denied Blue Origin’s arguments and sided with NASA and SpaceX on Thursday, handing Blue Origin its second defeat after it first protested the SpaceX contract unsuccessfully to a government oversight agency earlier this year. But his full order and the rationale it offered was sealed. Whatever the judge’s reasoning, Blue Origin has few other legal avenues to challenge the contract.

“Not the decision we wanted,” Mr. Bezos wrote on Twitter after the ruling, “but we respect the court’s judgment, and wish full success for NASA and SpaceX on the contract.”

A spokesman for Blue Origin said the company’s lawsuit highlighted what it considered “important safety issues” in NASA’s effort to award funds for a lunar lander “that must still be addressed,” but added: “We look forward to hearing from NASA on next steps” for future moon lander competitions under the Artemis program (Blue Origin won $25 million from NASA in September in a modest lunar lander design program).

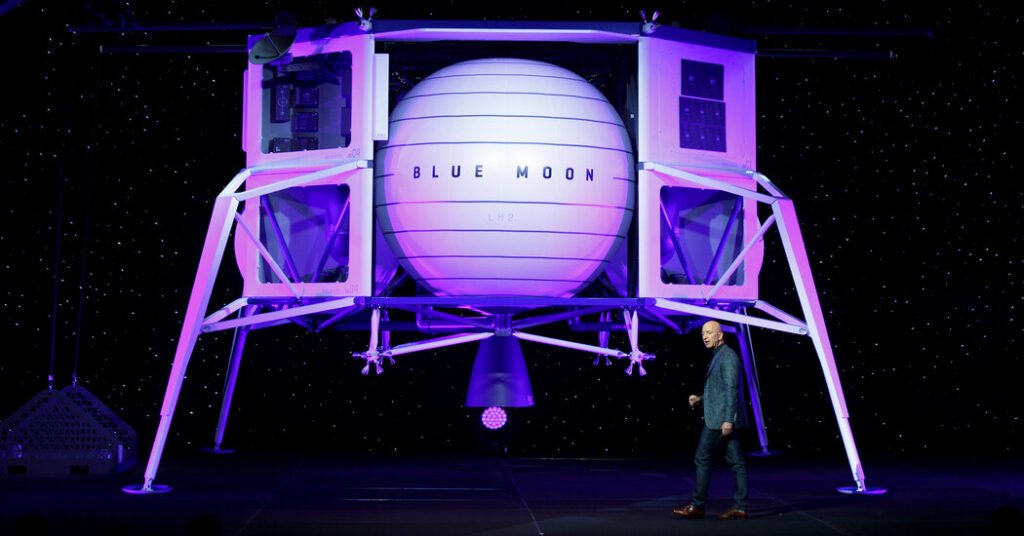

Blue Origin had partnered with Lockheed Martin, Northrop Grumman and Draper to develop and offer its Blue Moon lunar lander to NASA at a cost of $5.9 billion. It had hoped that assembling a team of aerospace heavyweights would be too good for NASA to turn down.

NASA initially wanted to pick two different lunar lander systems, in case one fell behind during development. But it was limited by funding from Congress, which last year allocated only a quarter of what the White House requested for the program. NASA ended up giving a contract to SpaceX alone, as the company’s bid was half the price of Blue Origin’s Blue Moon proposal.

The NASA funds, now unlocked by the agency’s court victory, will help fuel the whirlwind development of Starship, a fully reusable system that is the centerpiece of Mr. Musk’s ambitions to eventually send people to Mars. The company has been developing and test launching the rocket at its rapidly expanding facilities in South Texas. After several tests of the vehicle that ended in explosions, the company completed a high-altitude flight that landed successfully in May. In the near future, the company plans an orbital test of the spacecraft with no passengers aboard.

The NASA contract calls for two Starship trips to the moon and back, with the second mission carrying American astronauts. NASA’s stated deadline for the lunar landing, first announced by the Trump administration, is 2024.

But that was widely viewed as unrealistic even before Blue Origin’s legal challenges, which forced NASA to pause work with SpaceX while the litigation played out for six months.

In an initial Blue Origin protest with the Government Accountability Office filed in April, the company argued that NASA should have canceled or changed the rules of the program when it realized it couldn’t afford two lander systems (another company, Dynetics, filed a similar complaint). Rejecting that argument, the office ruled NASA had fairly evaluated the proposals. Although it agreed that NASA had improperly waived one requirement for SpaceX, that mistake was not serious enough to merit redoing the competition.

Blue Origin’s subsequent complaint in court focused largely on that NASA waiver, which let SpaceX skip certain government safety reviews to accommodate its novel plan to launch a dozen or so “tanker” rockets that would fuel up its two moon-bound Starship launches, legal filings in the G.A.O. dispute indicated. Instead of having a review for every launch, as NASA originally required, the agency allowed SpaceX to propose just three reviews in all: one for each moon-bound Starship launch, and one that encompassed all the tanker launches.

Blue Origin cited that waiver to support its claim that NASA gave SpaceX an unfair advantage.

During the litigation, Blue Origin waged a lobbying effort in Congress to pressure NASA into adding another company into the lander program. Its lobbyists sought to paint SpaceX’s Starship as risky and “extremely complex” in materials they distributed to lawmakers. SpaceX lobbyists countered, effectively casting Blue Origin as a sore loser and stating it plans to conduct reviews with NASA before each Starship launch.

But NASA resisted Blue Origin’s pressure and pointed to its goal of starting another lunar lander competition next year. What remains unknown is how much funding the agency will get for those missions from a Congress steeped in budgetary battles over President Biden’s social spending agenda.

And as competition in space between Mr. Bezos and Mr. Musk heats up and attracts more public attention, Senator Bernie Sanders of Vermont and other progressive lawmakers have waded into space policy, opposing extra moon lander money as part of their criticism of billionaires.

“They are in the wrong camp, and they don’t know it,” Lori Garver, NASA’s former deputy administrator under President Barack Obama, said of progressives who oppose providing more funds toward NASA’s moon lander programs.

She and other spaceflight experts point out that NASA’s funding model for the lunar lander and other programs makes the billionaire-backed space companies pay more of their own money than has been the case for NASA’s more traditional partnerships with Boeing, Lockheed Martin and other aerospace stalwarts.

“Members of Congress who are saying NASA needs a second competitor, and not giving money, are really just doing a disservice to the very agency they say they care about,” Ms. Garver added.

Whether Blue Origin gets a moon lander contract in the future, the company has set its sights on other goals. Last month, it announced a partnership to build a private space station, the Orbital Reef, as an eventual replacement for the International Space Station. It could be another way for Mr. Bezos to pursue the goal he said motivated the founding of Blue Origin: having “millions of people living and working in space.”