As the spread of coronavirus continues at an unprecedented scale, one of our most valuable assets is information.

The news cycle has become a consistent presence in our lives, whether it’s through the local TV bulletin, the Twitter notifications flashing on our phones, or the varied podcasts analyzing the crisis.

At a time of uncertainty, we turn to the news media to inform and guide us. But now, with more sources of news than ever at our fingertips – what do we choose to read? And, importantly, what do we choose to trust?

Our most recent study in the coronavirus series, available in our hub, seeks to find insights into some of these questions. You can also access the data for free in our platform.

We polled nearly 3,000 respondents in the U.S. and UK about their news consumption habits in the age of coronavirus – and here is what we found.

News is up, especially across TV.

Nearly half of U.S. and UK consumers say they’re watching more news coverage because of the outbreak.

This is the highest increase in any media consumption behavior we’ve tracked, and eclipses many entertainment-based habits like streaming TV content or listening to music.

But news comes in many forms, and investigating other emerging media behaviors indicates that its role may be even more significant.

According to our latest study, more than one-third of U.S. and UK consumers report watching more broadcast TV. This is – perhaps unexpectedly – more than the number of consumers increasing their online TV and music streaming consumption.

An influencing factor here is likely the prevalence of news on broadcast TV, especially the local variety. In both markets, there’s a direct relationship between watching more broadcast TV and having greater trust for the news that comes from it, like traditional networks (e.g. CNN, BBC) as well as local bulletins.

Levels of trust differ between nations.

While news is everywhere – on TV, in the press, on social media – not all news is created equal; especially when it comes to trust.

But trust is a fickle thing.

Crises test our trust in institutions, especially the media, as we scramble for information to make the right decisions. It’s unsurprising then that the media we trust the most to bring us news about the outbreak comes from governments, the World Health Organization, and established outlets like CNN and the BBC.

But there are important differences between the two markets. While the UK’s own government is the number one most trusted source of information for consumers, the case is not so in the U.S.

The U.S. government falls significantly behind the WHO in terms of trust.

Americans are 35% less likely than their UK counterparts to believe that their government is providing trustworthy information about the outbreak.

This represents a shift from our earlier research, which revealed that UK consumers were actually one-third less likely than Americans to say they trust how their government is handling the situation. And it’s likely this is a consumer reaction to what’s been happening in the U.S.

The administration’s position on the virus, its severity, and the government response has been constantly changing – undoubtedly leading to confusion and, ultimately, distrust among the public.

Social media is growing as a source of news.

The world of news media – whose very purpose is to bring truth to the masses – has been plagued by distrust for a number of years.

Terms like “fake news” are now part of our lexicon, and for a while now, social media has been firmly under the spotlight for its distribution of inaccurate information.

We saw consumers lose some of their trust in social media in the aftermath of data privacy scandals and Russian bots. But with the growing public health crisis, social media as a news source has made a resurgence.

Nearly half of internet users in the U.S. and UK are now reading more news stories on social media.

This is more than the number who are increasingly keeping in touch with family and friends, watching entertainment content, and sharing photos and videos – making news consumption the fastest growing behavior on social platforms.

Too much of a good thing?

While there’s growth in social media’s use-case as a news outlet, not everyone is so agreeable to this.

Nearly one-third of internet users across both markets say that they don’t trust social media for content about the virus. Between these two groups – those who use social media for coronavirus news vs. those who do not – there are telling differences.

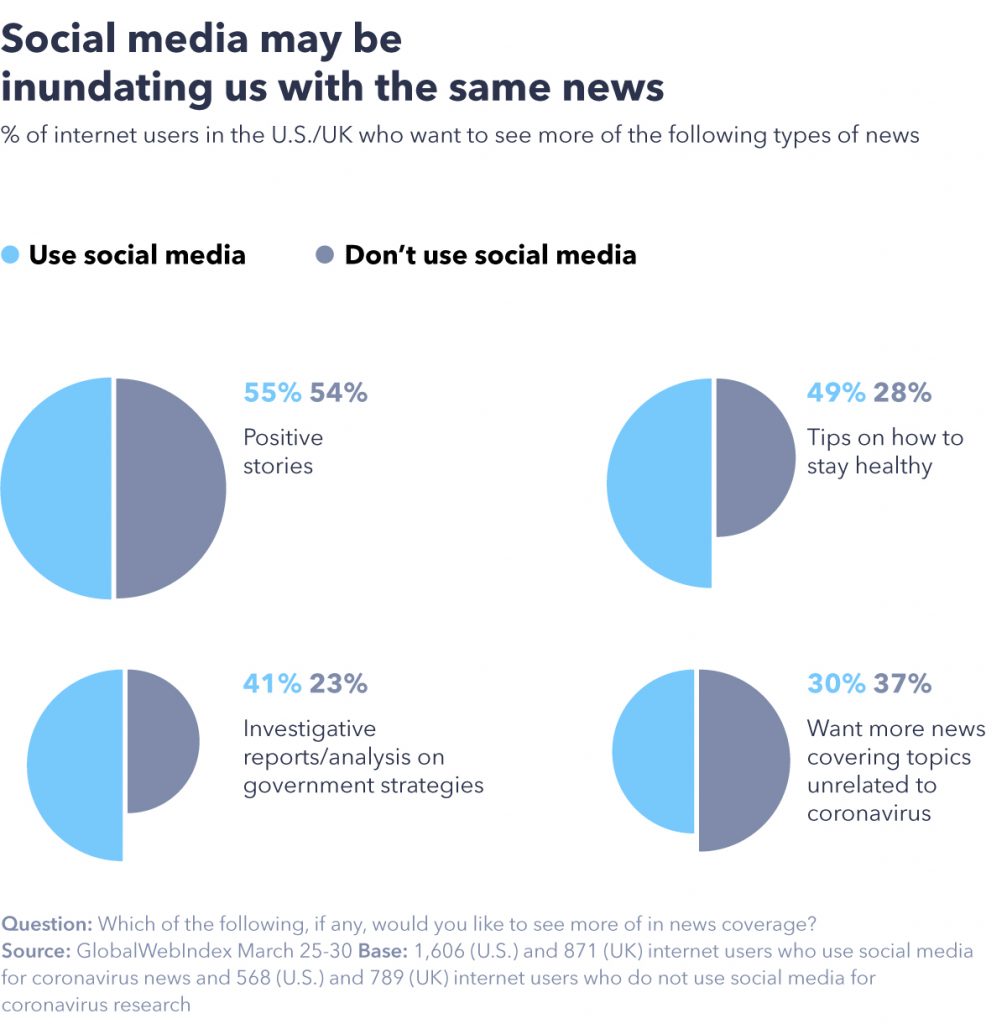

The first of these emerges in what consumers want to see more of when it comes to news.

Those who use social media to keep track of the coronavirus are much more likely to want more news related to the outbreak; 49% of these consumers want to see more tips on how to stay healthy, compared to 28% of those who don’t use social media for this purpose.

Additionally, users are 78% more likely than non-users to want to see more analysis on government strategies for curbing the outbreak.

In contrast, those who don’t use social media for coronavirus updates are nearly one-quarter more likely to want more news unrelated to the crisis, and local news tops their list.

The relationship between news and social media is an interesting one, and its sway on our own perceptions of reality.

Social media has often been called an “echo chamber” of opinions – the repertoire of accounts we cultivate often reflects our own ideological leanings, leaving less and less room for us to think objectively, to be challenged.

Perhaps the more we rely on social media to inform us in a crisis, the more consumed we become with needing to know what’s going on all the time? Does the day-to-day become a constant loop of refreshing our feeds, panicking, and then refreshing again?

A healthy dose of skepticism.

It’s perhaps impossible to answer these questions, but looking deeper into groups of users vs. non-users gives us a bit more insight.

On the issue of skepticism, it certainly seems that those less reliant on social media for their coronavirus updates have more of a critical eye.

Reports of infection rates have been a contentious point in the media, and the medical uncertainty of the virus has meant that we truly don’t know the extent of infection.

Just this week, the CDC concluded that as many as 1 out of 4 people infected will be completely asymptomatic but still contribute to transmissions.

Additionally, U.S. intelligence reports now suggest that China massively concealed the extent of the outbreak in their country – adding further fuel to the uncertainty of what sort of models we can expect to play out in other parts of the world.

Among all consumers in the U.S. and UK, opinion is divided as to whether infection rates reported in the media are accurate. 28% of consumers agree that reports are “extremely” or “very accurate”. 32% feel they are “accurate enough”, 28% believe they are “not very accurate” or “not at all accurate” and a further 11% are not sure.

These findings differ significantly between those who use and those who do not use social media to keep up-to-date on the crisis.

Users of social media are more than twice as likely to feel that reported infection rates are accurate, while non-users are more than twice as likely to say that they don’t know. Perhaps the less we trust news on social media, the less we trust news overall.

The importance of accuracy.

But what does this mean for news and media organizations?

Both in the long-term and in our current environment, the importance of accuracy cannot be understated.

This is especially true for social media platforms, where the flow of information is constant and essentially uncontrolled so maintaining a level of separation between what is news and what is opinion goes a long way in establishing trust.

And this is largely what consumers want and expect from these companies right now. As our earlier research shows, providing accurate and fact-checked information is the number one action people are demanding of social media companies.

Emphasizing this mindset across not just media, but any companies that are sharing insight and information, will serve both them and the consumers they want to reach.