Since it began selling its powerful smartphone spyware to governments in 2011, the Israeli cyber-intelligence firm NSO Group has cultivated an air of strict secrecy befitting its image as a haven for ex-military hackers. The company has tried to change its name multiple times, and when a Fast Company reporter called an NSO office in 2017, the man who answered said they didn’t speak to journalists, and hung up.

In recent months, however, NSO has stepped out of the shadows to defend its work, with a bold publicity campaign that includes on-camera interviews, a new website, and Google ads meant to populate web searches related to alleged abuses of the company’s spyware, known as Pegasus.

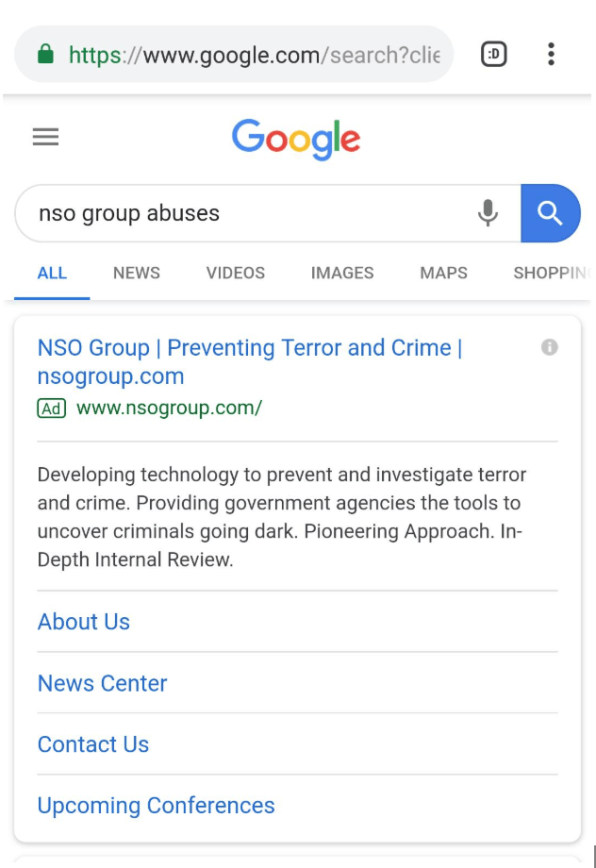

Several weeks ago, John Scott-Railton, a senior researcher at digital watchdog Citizen Lab, noticed that searching for “NSO Group” or terms like “NSO Group abuses” returned results with a prominent ad for NSO Group. The ad reads, “NSO Group | Preventing Terror and Crime,” and the website it links to touts products for helping to monitor “terrorists, drug traffickers, pedophiles.” The ad doesn’t mention the members of civil society–journalists, lawyers, activists and others–people whom Citizen Lab says have also been targeted by the spyware.

The ad also appeared when searching for “NSO Group Omar Abdulaziz.” Abdulaziz, a Saudi dissident whose phone was targeted by Pegasus, has claimed in a lawsuit against NSO that the spyware was used to surveil his friend, the journalist Jamal Khashoggi, before he was assassinated last year by government agents. Abdulaziz’s is the third legal claim brought by people who have been targeted by NSO’s cyberweapon.

Notably, the NSO ads do not appear in Google searches for “NSO Group Jamal Khashoggi.”

An NSO Group spokesperson told Fast Company that the ad campaign was tied to its new website.

“Like many companies, NSO purchased Google Search ads as part of our new website launch,” the spokesperson wrote in an email. “The ads are displayed to users who might want to learn more about NSO and our work helping intelligence and law enforcement agencies prevent and investigate crime and terror to save lives.”

Google prohibits ads for spyware and other services that enable “dishonest behavior.” A Google representative told Fast Company that it does not comment on individual ads, but confirmed that ads “selling” spyware are against its policies.

“We have strict policies that govern the kinds of ads we allow on our platform and ads selling spyware are not allowed,” the Google spokesperson said. “If we find ads that violate our policies, we remove them.”

The tech giant is familiar with the allegations of abuse surrounding NSO Group’s software. In 2017, Google security researchers helped uncover and disable a sophisticated version of Pegasus, which they said they had found on the phones of around three dozen people, many in countries with poor human rights records.

P.R. push

NSO’s web ad barrage is part of a larger media campaign. Company officials recently appeared on CBS’s 60 Minutes to defend the company’s work and show off its sleek headquarters in Herzliya, Israel, where employees—their faces hidden—could be seen winding down with video games and yoga.

In on-camera interviews, company co-founder Shalev Hulio and NSO Group’s co-president Tami Shachar repeated the company’s contention that its weapons are only sold in accordance with laws and for the purposes of stopping crime and terrorism.

Pressed on abuses, Hulio told Lesley Stahl that NSO had identified only three instances of misuse, and claimed that Pegasus had nothing to do with Khashoggi’s death. But Hulio did not deny selling Pegasus to Saudi Arabia, and defended the use of spyware on journalists in the course of criminal investigations.

“Now by themself, they– you know, they are not criminals, right?” the NSO co-founder said. “But if they are in touch with a drug lord… and in order to catch them, you need to intercept them, that’s a decision that intelligence agencies should get.”

NSO’s Pegasus spying software was reportedly used by Mexican authorities to capture one of the world’s most notorious drug lords, Joaquin Guzman, better known as El Chapo. https://cbsn.ws/2TWdTUD

Posted by 60 Minutes on Sunday, March 24, 2019

Hulio also implied that Pegasus was used by Mexican police to locate the drug lord El Chapo in 2016, a suggestion he made in an interview with the security reporter Ronen Bergman in January. In another appearance on Israeli television that month, the NSO co-founder lashed out at one of the lawsuits against the firm as “a public relations stunt.”

To help manage its publicity efforts, NSO has retained the services of SKDKnickerbocker, a Washington D.C.-based firm known for its work for Democratic and progressive political campaigns. But NSO’s efforts to defend its image have also reportedly included the use of more clandestine reputation managers.

In recent months undercover operatives have investigated critics of NSO, including two Citizen Lab researchers whose evidence sits at the center of the lawsuits. Israel’s Channel 12 and the New York Times reported in January that the operatives were linked with the Israeli intelligence firm Black Cube, which has become infamous for “dirty ops” campaigns, including against women who had accused Harvey Weinstein of sexual misconduct. NSO and Black Cube have denied any involvement.

Related: How a spyware-hunting PhD student foiled a private spy over lunch

Big publicity campaigns are unusual in the clandestine cyber-weapons industry. Motherboard pointed to two other known instances: A 2015 commercial for Hacking Team, an Italian company that also sells spyware to governments, and, a 2012 Bloomberg story that featured the managing director of FinFisher, a British-German hacking firm.

NSO’s image rehabilitation comes as the company comes under new ownership: Last month, the co-founders bought NSO back from a U.S. private equity firm with the help of Novalpina Group, a European private equity firm. A search for a $500 million loan to finance the purchase ended this month when the new owners said they had raised the money with support from Jefferies and Credit Suisse.

NSO, which also goes by the name Q Cyber Technologies, is now valued at just under $1 billion and has a “solid 20% growth in product bookings,” according to Calcalist, citing a report by S&P Global.

AdWords for spyware

NSO’s Google push reflects a basic strategy for online reputation management. Businesses regularly try to enhance the visibility of their web pages through aggressive search engine optimization techniques. Troubled brands use the same strategy to ratchet positive content to the top of search results to, at least in theory, neutralize critical content. Overcoming the sheer number and variety of reports on NSO Group would be daunting, so Google ad buys might well be the next best option for the company.

A Google representative declined to comment on NSO’s ads, but pointed Fast Company to policies against services that enable “dishonest behavior,” or “enable a user to gain unauthorized access (or make unauthorized changes) to systems, devices, or property.” That includes “hacking services, stealing cable, radar jammers, changing traffic signals, phone or wire-tapping.” The Google spokesperson said that the company reviews all ads.

Google’s inaction on NSO Group’s ads suggests that the ads are permissible because NSO isn’t actually selling its spyware within the ad. When asked if companies that sell spyware to governments can buy ads if they don’t advertise the product itself, the Google spokesperson declined to comment.

The ads may technically meet the company’s ad policies, but Google has sought to block NSO’s spyware in other ways.

In 2016, after an investigation by Citizen Lab into Pegasus prompted Apple to release a security update for iPhones, Google began investigating a sophisticated version of the spyware capable of gaining root access to Android phones. Working with cybersecurity company Lookout, Google said traces of the spyware, which it called “Chrysaor,” had been found on “a few dozen” smartphones in 11 countries, predominantly in Israel, Mexico, Georgia, and Turkey.

In their 2017 report on the Android Developers Blog, Google researchers noted how the company attempts to improve its systems and protect users from “Potentially Harmful Apps.” Google didn’t identify the targeted individuals, but said it had “contacted the potentially affected users, disabled the applications on affected devices, and implemented changes in Verify Apps to protect all users.”

Related: The Secretive Billion-Dollar Company Helping Governments Hack Our Phones

In its own report at the time, Lookout was more blunt about the dangers of by NSO’s software.

“We are publishing this information to underscore the campaign’s novel ability to combine and integrate a series of malicious techniques to spy on victims while remaining hidden, both to the victim and to the security community at large,” Lookout researchers wrote. “Pegasus will likely always be a targeted threat, highly damaging to its victims’ privacy, as well as to any personal and business-data accessed on (or discussed near) the device.”