Few people sacrifice themselves as completely as Dian Fossey did for the mountain gorillas of Africa. She fought tirelessly to protect them from poachers, cattle herders, zoo kidnappers, corrupt governments, and tourists. Dian left a comfortable life behind to make the misty slopes of an extinct volcano her home and headquarters. There, she patiently sought out the gorillas, mimicking their facial expressions and actions until they grew curious about her. Eventually, she had their complete trust and friendship, and considered them her family.

Dian spent eighteen years on and off living among the gorillas. She continually risked her health, life, and reputation to raise awareness of their plight and save them from extinction. While the mountain gorilla remains an endangered species, Dian’s research and conservation efforts have greatly contributed to their increased population in the years since her death.

A Lonely Childhood

Dian Fossey was born in San Francisco in 1932. Her parents divorced when she was six, and her mother Kitty remarried a year later. Richard Price was a stern and distant stepfather who made Dian eat her meals in the kitchen with the help.

Lonely and frustrated, Dian turned to animals for emotional support. She was only ever allowed to have a goldfish, which was not replaced upon death. But Dian’s interested in animals continued unabated. She started riding horses as a child, and became a decorated equestrienne in high school.

Dreaming of Africa

The Prices refused to help Dian with college expenses once she eschewed the business path her stepfather laid out for a pre-veternarian program. She held various jobs and worked on a dude ranch in Montana, until she caught chicken pox and had to quit. She also had to quit the vet program, because she was terrible at physics and chemistry. She wound up getting an occupational therapy degree and working at a children’s hospital in Louisville, KY.

Still in love with animals, Dian was interested in Africa because she wanted to watch them roam free in habitats unspoiled by human contact. In 1960, a friend she’d made in Louisville went on safari and invited Dian along. She declined because she couldn’t pay her own way. At this point, Dian started saving to go to Africa. She wrote to her mother about it, thinking maybe the Prices would throw some money her way. They didn’t. In fact, they were horrified by the idea.

Dian wanted to go to Africa so badly that she used all her savings and took out a three-year bank loan to finance the trip. This upset her entire family. She assured them she would make her money back by selling articles and pictures about her experiences.

Meanwhile, Dian learned everything she could about Africa. She studied Swahili, safari guides, and the pioneering studies done by George Schaller, an American zoologist who had studied the rare mountain gorillas of the Belgian Congo in the 1930s.

Dian decided to add a couple of weeks to her safari to visit the Virunga volcanoes in Central Africa where the mountain gorillas lived. The Virungas comprise a chain of eight mostly-extinct volcanoes. The gorillas live thousands of feet in the sky, so high that the rain forest is cold and misty for most of the year.

Dian worried about how her allergies would react to this vastly different environment. Throughout her life, she had suffered many bouts of pneumonia and several asthma attacks, and was a smoker to boot. When she finally left for Africa, part of her safari luggage included forty pounds of various medicines.

A Lucky Break

Dian left for Africa in September 1963. She’d hired a guide by mail who was to drive her to Kenya, Uganda, the Congo, and Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe). His usual clientele were big game trophy hunters, so the two didn’t get along very well. She wore him out, constantly taking pictures, asking questions, and making him drive all over the place in search of the animals she wished to see.

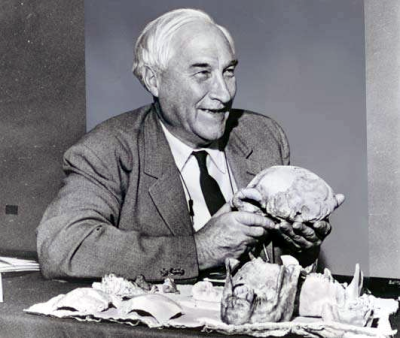

As part of the safari, Dian was hoping to meet Dr. Louis Leakey, a renowned paleoanthropologist who started finding hominid fossils in the early 1930s. He established that humans were older than previously thought, and originated in Africa rather than Asia. In 1960, Leakey helped established Jane Goodall’s long-term study of chimpanzees in Tanzania.

By this time, Leakey was very famous and hard to pin down for an interview. So Dian decided she would just go to his camp and hope to run into him. She got lucky. Leakey was strolling the grounds and saw her. He seemed enthralled with her, and decided to give her a chance to explain herself.

She told him she wanted to study the mountain gorillas in the Virungas, and hoped to make her home there one day. He invited her to tour the local archaeological dig. While straining to get a picture of a giant giraffe fossil, she fell into the pit, broke her ankle, and vomited from the pain. Leakey and his wife took great care of her, and he told her to go see the gorillas if she could manage the ankle.

Dian’s guide initially refused to take her into the Congo because of political turmoil in the region. Also, he would need extra insurance on his Land Rover. Eventually he relented. They took a long hike up Mt. Mikeno and saw a group of six gorillas. At that moment, Dian knew that one day, she would return to study the gorillas.

Joining Leakey’s Angels

After the safari, Dian went back to Louisville and her job at the children’s hospital. She wrote several articles about her trip and sent them out to national magazines. None of them accepted, but the Louisville Courier-Journal published her stories and photos about the gorillas and meeting Louis Leakey.

A few years later, Leakey was on a lecture tour that went through Louisville. Dian stood in line afterward to talk with him, armed with her articles. To Dian’s surprise, he recognized her, and they discussed her experience with the gorillas. He told her she might be just the person to start a long-term study of the gorillas in their habitat.

Dian was afraid that her lack of scientific education would hinder her chances of being chosen, but Leakey told her he preferred field researchers without preconceived notions of what they would observe and experience. Once he secured the funding, she would be headed back up the mountain.

On Safari to Stay

Dian left for Africa again on December 15th, 1966, three years after her first safari. She would be funded in part by National Geographic, who was going to give her the Jane Goodall treatment: a TV special, magazine series, money for pictures that would appear in Nat Geo, and a contract to write a layman-level book based on her experiences with the gorillas.

She quickly learned to track gorillas from Sanweke, a Congolese tracker who’d worked for George Schaller. He taught her to study tree branches to detect movement and direction, and to look for knuckle prints in the ground and chains of dung left by groups of gorillas on the move.

The first time she made contact with the gorillas, it was with a group of nine. To get the gorillas accustomed to her presence, Dian used George Schaller’s research as her playbook. She tried to arouse their curiosity by imitating their facial expressions and gestures. To prove she was friendly, she walked on her knuckles and ate wild celery stalks.

It worked. She eventually made physical contact, and by then she had a professional photographer there to immortalize the moment for National Geographic. Soon after, she was allowed to play with and even cuddle the baby gorillas.

Poachers and Politics

Almost from the start, Dian had problems with poachers. Even though it was illegal by park rules, they hunted forest antelope and other game to stay alive and feed their families. Once the novelty of her being there had worn off, she had problems with camp workers and guards disobeying her, lying, stealing, complaining, and shooting at elephants who were merely grazing.

Dian wrote to Louis Leakey asking for help. She had a lot of loneliness, doubts and fears due to her isolation, and being bullied by the workers. But still, she was thrilled to be where she was.

In July of 1967, the Congo fell under a state of siege. Dian got a letter from the park director stating that they were going to come remove her from the mountain because it was no longer safe for her. They weren’t giving her a choice.

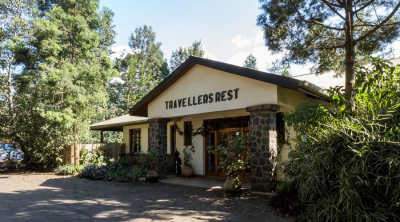

Rebel soldiers from Zaire came and dismantled her tent, and they held her in Rumangabo for two weeks. Then she tricked the soldiers into taking her to Kisoro, Uganda to settle a made-up registration issue with her Land Rover. She fled to the Travelers Rest Hotel at the foot of the Virungas, where she had stayed during her first safari. The owner notified the Ugandan military, who arrested the rebel soldiers.

The Other Side of the Mountain

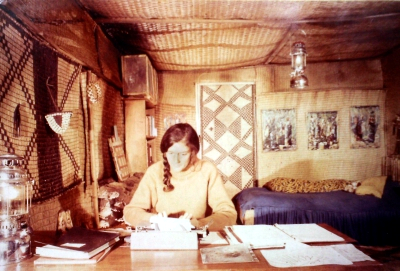

Dian discussed her options with Louis Leakey, and chose to resume her studies on the Rwandan side of the Virungas. On September 24th, 1967, Dian pitched her tent in Rwanda, officially founding her new camp. She named it Karisoke after the two mountains it’s nestled between—Karisimbi and Visoke.

Dian hired locals to help her do everything from tracking gorillas to camp chores. Within a few years, she had students from all over the world coming to Karisoke to work on a census of the gorillas.

Worried that she wouldn’t be taken seriously without scientific credentials, she applied to the zoology program at Cambridge. They accepted Dian as a PhD student in 1969, and she split her time between England and Karisoke. While she was away, she left student researcher Alexander (Sandy) Harcourt in charge of the camp.

Gorillas Are a Girl’s Best Friend

Of all the gorillas she encountered and befriended, Digit was the dearest to her heart. He was about five when she found him, and had a broken finger, thus the name. Since there were no other gorillas his age to play with, Dian became his playmate. Over the next several years, she watched him grow and mature into an independent gorilla.

A group of poachers stumbled upon Digit’s group in late 1977. He bore the brunt of their attack so the others in his group could get away. Digit was speared several times, decapitated, and his hands were cut off.

Dian immediately established The Digit Fund to raise money for gorilla conservation efforts. Isolated as she was, it was difficult to do much other than write letters. She still had the Rwandan government to deal with, and they were more interested in conservation through tourism than they were in Dian’s anti-poaching patrols.

Black Magic Woman

Dian was vehemently opposed to poaching, which was illegal in the Park. But the guards didn’t get much pay, and they were easily paid off by the locals, who were just trying to survive. The poachers were usually after antelope. Gorillas were mostly collateral damage, although some poachers killed them for their heads and hands, which they later sold. She was also against cattle herding through the park, because the herds destroyed the plants the gorillas eat and often drove the gorillas to higher ground where they can’t function as well.

Dian took serious measures against both poaching and herding, which earned her some enemies. Some were her students, who were against the constant patrols to cut down snares and destroy traps. Sometimes she and her workers and a few of her fellow researchers caught poachers and imprisoned them for short periods. Dian got a bit of a reputation as practicing witchcraft because she would give imprisoned poachers her version of a black magic show, which consisted of dime store magic tricks performed in garish, terrifying Halloween disguises she’d bring back from the States.

Dian’s behavior caused a rift between her and several of her students, particularly Sandy Harcourt. Sandy sided with the Rwandan government, who wanted to turn Karisoke into a tourist facility. He helped them establish the Mountain Gorilla Project, an organization that used Dian’s and Digit’s names to raise money, but funneled it all into tourism promotion.

The Curse of Death

Dian went to Ithaca, NY in 1980 as a visiting professor at Cornell, and used the next three years to finalize Gorillas in the Mist between lectures. Then she went on a book tour. She raised a lot of awareness along the way, and learned a few things herself, as person after person told her about the thousands they’d donated to the Mountain Gorilla Project.

By the time she returned to Karisoke in 1983, it was in shambles and running on fumes. She started paying maintenance and payroll costs from her book proceeds. No sooner than she’d fixed the place up a bit and got the anti-poaching patrols going again, she had to jet off to another lecture tour. By this time, she was really feeling pressure to leave Rwanda and wondered how many more times they would renew her visa.

Soon after putting together a group of doctors and veternarians to look into a spate of recent gorilla deaths, Dian found her two gray parrots poisoned and on the verge of death. Days later, she found a wood carving of a puff adder on her cabin doorstep. She knew well enough what this meant: the curse of death was upon her.

On the morning December 26th, 1985, Dian was found murdered in her cabin, her face split diagonally with a machete. Her murder remains unsolved, though many believe it was the work of poachers.

A Living Legacy

Dian’s gorilla conservation efforts continue to this day. In 1992, the US branch of the Digit Fund became the Dian Fossey Gorilla Fund International. Following the Rwandan genocide, Karisoke was moved to Ruhengeri, where research continues. Though the mountain gorillas are still endangered, their population continues to rise. And hope comes in many forms—back in 2012, two young gorillas were spotted working together to destroy a poacher’s snare.