When Ellen Swallow Richards became the first woman to graduate from MIT in 1873, she was convinced that her aptitude for science was not unusual–that she was not, as people claimed, an “exception.” Richards had graduated from Vassar in 1870 and was admitted to MIT to study chemistry in January 1871, when opportunities for women to gain hands-on laboratory experience were limited. The Institute considered her a special case, but Richards was determined to prove that other women would eagerly pursue scientific enquiry if given the chance.

In 1867, MIT professors had begun offering free laboratory sessions to the general public through an initiative called the Lowell Free Courses of Instruction. Because these demonstrations were open to the public, women were not barred from taking part, even though they could not attend the Institute as students. Several local female chemistry teachers had jumped at the opportunity.

Those free laboratory exercises were on hiatus for the winter of 1872-’73, though, when a young woman from a medical college arrived in Boston hoping to sharpen her quantitative analysis skills. She applied to attend a class at MIT with Professor James Mason Crafts, a chemistry instructor, but he “saw no suitable way of accommodating her in his already crowded rooms,” Richards later wrote. The young woman would have been out of luck had it not been for the Woman’s Education Association (WEA), a group of educated, largely wealthy Boston women formed in December of 1871, and the efforts of Richards herself.

Dedicated to bettering women’s education, the WEA came to the woman’s aid, securing a space in the chemistry lab in the local Girls’ High School on West Newton Street in Boston, as well as the funds to supply it. In the winter of 1873, 16 women came together for a special advanced chemistry class.

Under the direction of Professor Crafts, Richards, who was then still a student at MIT, and Bessie Capen, a local school-teacher and WEA member, taught the course without pay. This was the first time the WEA and Richards combined forces in what would prove to be a fruitful partnership. The class in the Girls’ High School laboratory acted as a powerful proof of concept–if provided the opportunity to study science, women would come.

Over the next few years, women frequently applied to study at MIT for short periods. For instance, teachers might apply for a couple of months’ instruction in quantitative analysis to qualify for better teaching positions. But the Institute still hadn’t opened its doors to women as regular students. Richards was keen to see a dedicated space for women on MIT’s campus, and she wanted MIT to establish a permanent class similar to the one that had been held in the Girls’ High School.

The tide was turning in her favor. In the winter of 1876, so many women applied to attend the Lowell lectures that MIT’s chemistry professors took eight female students into their own private laboratories free of charge. That year, Richards stood before a session of the WEA and announced her plan for a Special Laboratory for Women.

“When you gave a small sum of money for a Class in Chemistry at the Girls’ High School three years ago, you doubtless did not anticipate these results,” she said. “But that Class demonstrated more fully than any previous one, the ability and interest of women in this Science.”

With the WEA’s support, Richards petitioned MIT to provide space for a Women’s Laboratory in the Walker Building, a proposed new facility that would expand MIT’s Boston campus. When the building’s construction was delayed, an alternative space was identified, and the Institute determined that it would need $2,000 for the lab’s instruments and apparatus. The WEA raised the money within three weeks. When a change of plans called for the Women’s Laboratory to occupy a larger space–in a five-room annex of the Rogers Building, MIT’s original building on Boston’s Boylston Street–the WEA rapidly provided an additional $500 to cover the extra costs. The annex was outfitted with a chemical laboratory, a library and weighing room, a reception room, and industrial and optical laboratories.

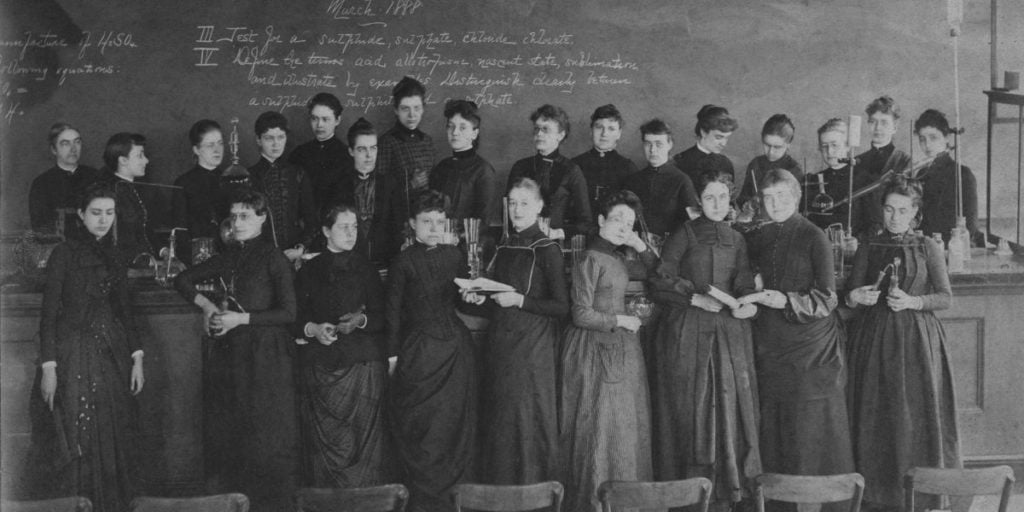

The MIT Corporation voted to admit women as special students to study in the laboratory, and on October 5, 1876, its opening was officially announced. Under the direction of John M. Ordway, the lab offered “the advanced study of Chemical Analysis, Mineralogy, and Chemistry as related to Vegetable and Animal Physiology and to the Industrial Arts.” Any woman interested in such an education was invited to apply.

On October 23, the Women’s Laboratory welcomed its inaugural class of 23 students. A year later, Richards couldn’t help but gloat in a speech to the WEA, since some at MIT had predicted she wouldn’t even get 10. “It is always pleasant to have our prophecies fulfilled,” she said, “and especially pleasant when some doubt has been expressed as to the probability of fulfillment.” Chemistry teachers made up most of the first class, but Richards was especially satisfied that an aspiring physician and a budding mineralogist were among their ranks.

Richards taught chemistry and mineralogy at the lab for several hours a day all seven years it was open, though her name was not officially listed in the course catalogue until 1878 and she was not paid. (She wouldn’t be placed on MIT’s payroll until 1884, when she received an annual salary of $1,000 to instruct a sanitary chemistry course). Her co-instructor at the Girls’ High School, Bessie Capen, was one of the lab’s first students. In 1878, Capen and a classmate became the third and fourth women to earn bachelor’s degrees from MIT.

In all, the Women’s Laboratory served 102 women, and many went on to earn MIT bachelor’s degrees. It closed its doors in 1883 when the annex the lab had been housed in was torn down to make room for the construction of the Walker Building, which would contain brand-new laboratory spaces for the study of chemistry.

With the closure of the Women’s Lab, the future of women’s education at MIT was uncertain. But Richards saw an opportunity. “The only objection now urged by the officers of the Institute to the admission of women to full privileges in all courses is lack of room,” she wrote. She and the WEA once again advocated for constructing the Walker Building with women in mind so they, too, could use the laboratories. When MIT administrators resisted the idea, citing the prohibitive expense, Richards simply asked how much money was needed. Upon learning that it would take $8,000, the WEA again sprang into action and soon raised the funds. The money covered the cost to construct the new building with more laboratory space, a private women’s reception room (which would be known as the Margaret Cheney Reading Room), and toilets for women. On September 29, 1883, the Corporation voted to admit students to the new building’s chemistry laboratories “without distinction of sex.”

Richards would continue to be a champion for women at MIT throughout her career. She cofounded the MIT Women’s Association, an organization promoting fellowship among MIT women, in 1900 and was elected president every year for a decade. In 1911, she was voted permanent president of the Women’s Association–a mark of the respect and admiration she’d earned from the women who followed in her footsteps.