Sam Walton was one of the great American bootstrappers. The founder of Walmart raised an icon of American commerce on a foundation of determination and smarts. Princeton professor Derek Lidow is the first researcher granted access to the Walmart Museum’s archives, whose wealth of documents, memorabilia, and oral history videos he draws on for his new book, Building on Bedrock: What Sam Walton, Walt Disney, and Other Great Self-Made Entrepreneurs Can Teach Us About Building Valuable Companies. Lidow uses Walton’s principles and strategies, together with the experiences of other great founders to guide aspiring entrepreneurs on their quests. The following is an excerpt:

By opening day, the team felt fried. For two weeks they had worked long hours to get Sam Walton’s second Walmart ready. Rebuilding and installing old fixtures salvaged from a store recently gone bankrupt had been a struggle. Late into the night the team had unloaded truckloads of merchandise. By morning they had barely finished placing products on shelves, on tables, and in front of the store. On top of that, the July heat was punishing; the building wasn’t air-conditioned; the restrooms didn’t work; and the parking lot wasn’t fully paved.

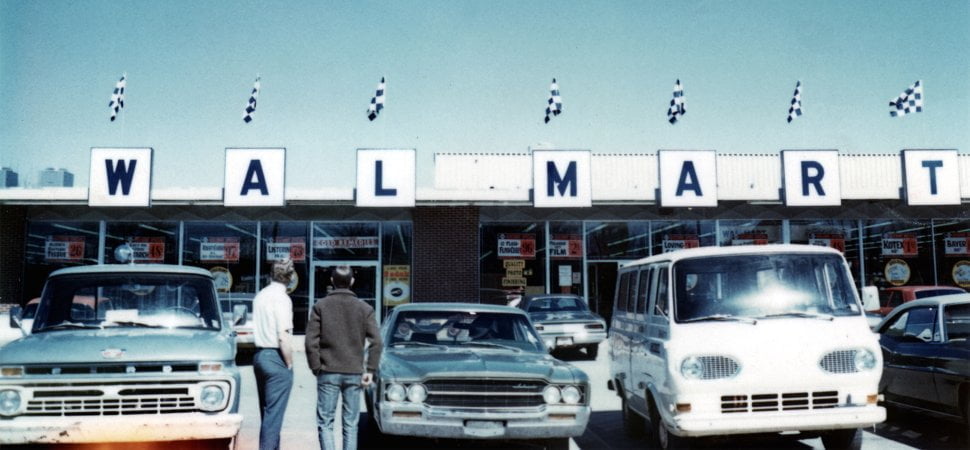

CREDIT: Courtesy Diversion Books

A great deal was at stake. Store number one had struggled to make money and was not as successful as Sam had hoped. He had borrowed as much as the bank would loan him, using everything that he and his wife owned as collateral. He needed his second Walmart to prove that a discount retail chain focused on small towns could be highly profitable. If store two performed like store one, Sam and his team would have to put their growth plans on hold.

To attract as much attention for the opening as possible, Sam advertised great deals on brand-name staples like toilet paper and detergent. To give the event a family feel, he arranged free donkey rides for kids in the parking lot outside the main entrance. He also bought every ripe watermelon that farmers within a day’s drive could deliver. The team had piled melons four feet high along the front of the store. They also piled them along the unpaved areas of the parking lot to keep out customers who might trip over the old wooden forms still lying around.

It was the hottest day of summer, with temperatures in the upper 90s. But the heat didn’t keep away the crowds. Drawn by the advertised low prices, they began lining up even before the store opened at 9 a.m. The team worked with hardly a break all day, manning cash registers and replenishing shelves, tables, and floors with items that were disappearing as fast as they could be restocked.

Amid all the excitement, no one seemed to notice that some of the watermelons were breaking open in the heat, their juices flowing onto the sidewalk and into the parking lot. Nor did they care that the man running the donkey rides was too busy to pick up his animal’s droppings. Over the course of the day watermelon juice and donkey dung covered growing portions of the sidewalk. The acrid mix was soon tracked inside and permeated the store.

Perhaps the only person who did notice was David Glass, a top financial officer of a well-established Midwestern drug store chain. David’s company had heard that Sam Walton had some interesting ideas about attracting and exciting customers; and he had driven from Missouri to Bentonville, Arkansas to see for himself. At the Walmart, David was appalled by the manure and burst watermelons and by the sight of merchandise piled high on tables instead of laid out neatly on shelves. He reported back that the opening was the worst he had ever attended. Anyone in his company who ran an opening like the one he had just witnessed would have been fired on the spot.

But David had missed the real story. Judging the opening by conventional big-city retail aesthetics, he had ignored the crowds of customers and long lines at the cash registers. By contrast, Sam and his team knew that in the rural heartland everyone was used to animal smells. In fact, they would feel more comfortable in a humble looking–and smelling–store. And Sam understood that the way to make people happy was to make their dollars go farther.

That Midwestern drug store chain went out of business long ago. But not before David came to appreciate Sam’s insights into pleasing customers. He later joined Walmart and became an exemplary student of Sam’s philosophy. Eventually David became Walmart’s CEO.

Sam Walton is among a number of entrepreneurs who provide a useful corrective to what we think we know about starting a business. Yes, Walmart is now one of the most valuable companies in the world. But its success had nothing to do with network effects or venture capital. Rather, Sam absorbed and practiced some hard and humble truths about entrepreneurship that have gotten lost amid all the publicity about a few young Silicon Valley billionaires. They are truths that would-be entrepreneurs and their loved ones ignore at their peril.