For years, an unresolved question for those drilling horizontal wells has been: Does it matter if it is toe-up or toe-down?

Horizontal wells generally follow an up or down slope following the most productive rock with some large changes in elevation from the heel—the curve from vertical to horizontal—to the toe.

Results from modeling did not settle the matter. Recently, Devon Energy offered its response based on the performance of more than 300 similar wells drilled in the Cana-Woodford Shale in Oklahoma.

The comparison was possible because the company had mass-produced similar wells, giving it a large sample of wells to study with 4,800-ft laterals where it fractured 10 stages with 40 perforation clusters using 3.5 million lb of proppant located in a compact area with similar geology in the three depths studied.

The analysis was done in a way that ensured, as much as is statistically possible, that “only toe-up or toe-down could be affecting the production performance of the wells analyzed,” said Sam Browning, a reservoir engineering for Devon who delivered the paper at the 2016 Unconventional Resources Technology Conference.

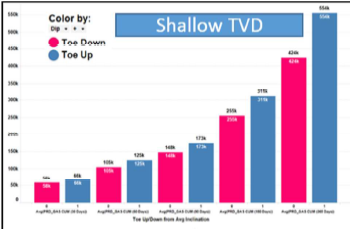

It concluded that toe-up wells produce more. And the greater the elevation change between the heel and the toe, the greater the impact.

“The more toe-up they are, they [wells] appear to be better, and the more toe-down is worse,” Browning said, adding “All the best wells were toe-up.”

|

Shallow Zone

|  |

|

Middle Zone

|  |

|

Deep Zone

|  |

Devon found the toe-down wells produced 25% less based on a year’s worth of production, he said. The difference was narrow in the early days of production and widened over time.

The results were compared based on the depth of the wellbore—shallow, middle, and deep—because of differences in the zones. For example the condensate-rich production in the shallower zone could be less able than the gas-prone deep zone to clear the well during flowback after fracturing and overcome liquid holdup.

The widest variation between toe-up and toe-down wells was seen in the middle zone where the elevation changes were greatest. In those toe-down wells, the elevation changes were nearly all in the 100–200 ft range, while the dips at other depths were less than100 ft.

The paper predicted an extreme toe-down well in the lowest-pressure area would produce 30% less over its life.

The paper suggested toe-up wells may perform better by offering a gravity boost for the liquids-rich flow, and toe-down can allow liquid to build up in the production zone, hindering production.

Browning is planning to come back to these wells to see how they are doing in the future, which will address questions about whether changes that come with age, such as increased water production requiring pumping, will alter the conclusion.

Devon is using this study when planning new wells in other areas with similar conditions, such as projects to drill infill wells.

In some places, the only practical alignment for the well may require drilling a well toe-down to stay within the most productive rock, which is a critical variable.

And the sample size in this case is too small to generalize about all horizontal wells. But based on the Devon study, the potential reward for knowing if toe-up is better or worse can be big enough to justify the cost of a study to answer the question.