You’re being stalked around the clock.

A growing array of electronic devices—including your smartphone, tablets, speakers and smart TVs—are acting as magnifying glasses for companies that pay billions of dollars to get an up-close and personal view of you.

The information is fed into profiles used to target you with ads, classify the riskiness of your lifestyle, help determine your eligibility for a job and much more. Mounds of personal data are flowing to political consultants attempting to influence your vote, government agencies trying to find lawbreakers and scammers trying to trick you.

But the way most people feel the results day to day is through marketing.

Christopher Day knows better than most how intrusive technology can be.

He’s the founder of an Indianapolis tech company, DemandJump, that uses artificial intelligence to help companies identify customers and send them the right messages to procure sales.

But Day has also been a victim of what he calls annoying and even creepy cyber-marketing—strategies that are different from those employed by DemandJump.

Late last year, Day was thinking about buying a Peloton, a popular indoor exercise bike. He had never searched for nor discussed Peloton online or in emails. He had never contacted the manufacturer or a retailer about the product.

But with his smartphone in his pocket, Day discussed the bike with friends at a holiday party. And he believes his phone—either through the operating system or an app he installed—was listening.

Suddenly, he began receiving digital ads for Peloton across his devices.

“That feels too invasive,” Day said. “That made me not want to buy the product. And I didn’t.”

But despite the marketing fail with Day, many advertisers are relying on these and other cyber tactics to get their products in front of customers—repeatedly.

Everything you do with your electronic devices is monitored, tracked, reported and stored. And all that information is saved indefinitely, ready to be rolled out at a moment’s notice to help a company make a sale.

While consumers can take some steps to stem the peeping, it’s tough to stop the data gathering completely without going off the grid—a difficult move given that the tools that make life convenient today are the very ones marketers exploit.

Cookie monster

Companies build profiles about customers and track them in a number of ways. But the most important ingredient might be cookies—and not the edible kind.

Cookies are bits of programming that operate in the background of a website, app or device.

The name is derived from the term “magic cookie,” which is what programmers in the late 1970s called a packet of data a program picks up from a user’s computer and sends elsewhere for identification purposes. Cookies grab what’s called an IP address, an identifying number assigned to every device on an internet-connected network. But cookies don’t necessarily know the user or owner of that device (although, as you’ll see, those dots aren’t difficult to connect).

Cookies have some important, practical functions. For example, they let web servers know whether someone is logged into a site, and which account they are logged in with. IBJ uses cookies, for example, to help determine whether a reader on its website is a subscriber.

But programmers have discovered even more valuable marketing uses for cookies. Ever wonder how you can leave an online store—or close your browser or turn off your computer entirely—and come back a few minutes, hours or even days later to find the contents in your shopping cart still there? Or how an airline knows about a reservation you started but didn’t complete?

That’s information the web browser deposited on your computer with a cookie. When you go back to the site, the computer reads the cookie and distills the information from your previous visits.

And that’s just the first crumb of what cookies can track. They can tell a site what pages you looked at and for how long, what items you clicked on and even where you put your cursor. Some can even track—through your webcam—where you trained your eyes.

But not every cookie is created—or accessed—equally.

Cookies deposited on your computer by a website operator are called first-party cookies. Generally, first-party cookies can be read—in their entirety—only by the website that deposited them.

Website developers say those kinds of cookies help them customize content to suit you. Think ESPN.com, which uses cookies to track your browsing, reading and viewing, then recommends other stories.

Third-party cookies are another story entirely. They are deposited by ads, online quizzes, games and other content users download or visit. So if you click on, say, a Nike ad and then go to the Nike website, the site will retrieve that cookie to get a better idea of who you are and how you like to shop.

Tracking your every move

But why, after you search for a product or click on an ad, do ads for those and related products begin popping up—no matter where you surf?

Enter data brokers and trackers—a vast and growing network of companies that are not only depositing cookies but also selling that information to a wide range of retailers, service providers and websites. A national or global company might subscribe to a dozen or more data brokers and others services to track current and potential customers.

Say you go to a car dealer’s website and then surf to a news site. If those two sites subscribe to the same ad network—or network of networks—then, voila, you’ll see an ad for the very vehicle you were researching, even though the story you’re reading has nothing to do with cars.

“It’s like you once stopped in a car dealership, but now you’re at the grocery store and someone is chasing you around the grocery store yelling at you to see if you want to buy a car,” said DemandJump’s Day. “In real life, internet marketing methods might be considered harassment.”

DemandJump doesn’t rely on cookies, Day said. It uses math and artificial intelligence to make sure companies have access to consumers in the “buying mode” of their product. It’s a complicated business that relies on programing to recognize the precise wording of search queries.

But thousands of companies use cookies, and so, as you travel from website to website, you are taking on cookies like a well-traveled ship takes on barnacles.

“Your IP address is being collected by every single network you pass through, and that includes services like Netflix,” said Warren Sifre, principal consultant for Moser Consulting, an Indianapolis-based information technology company that specializes in business intelligence and advanced analytics.

Free software and apps are huge data-gathering tools.

“There is a reason why things are free,” Sifre said. “It wouldn’t make much business sense to develop an application that had zero return on investment, whether it be directly or indirectly.”

The combination of millions of cookies and huge data brokerages means retailers and other companies can divine within a second of your landing on their website where else you’ve been on the internet and everything you’ve clicked on, read, viewed or listened to—sometimes for years, even a decade or more.

“People don’t appreciate the permanence of this data,” said Brian McGinnis, a partner in the local law office of Barnes and Thornburg and a cybersecurity expert. “There’s a reason why some companies are building massive data centers. The internet doesn’t forget.”

Getting personal

Combine cookies with personal data—your name, birthdate, hometown and more—and the outcomes become very personal.

Among the ingredients is Facebook—and its forerunner, MySpace.

When the first major social network, MySpace, came along in 2003, it seemed like a great way for people to stay connected to family and friends. But marketers—and social media sites themselves—quickly realized the value of the information it was gathering. Then came Facebook, with its worldwide reach, which took personalized marketing to a new level.

Social networks have induced people to voluntarily cough up the information marketers have long coveted: name, residence, age, occupation, nationality, dating status, hobbies, vacation destinations, you name it. And all that information can be easily attached to the IP address of your laptop, tablet or, increasingly, your smartphone.

And Facebook has made a tidy bundle of cash selling that data. Though the company won’t disclose the amount, multiple tech sources estimate the world’s biggest social media network makes $10 billion annually selling data.

Through your device’s IP address, data brokers, trackers and ad networks can not only know all about you, but also where your device is at any given time—almost down to the square foot. More on that later.

But this treasure trove of data doesn’t all come from Facebook.

There is another cadre of companies whose sole mission is to scrape every imaginable piece of your personal information—even some you might not imagine—from online public records and sell it to the highest bidder.

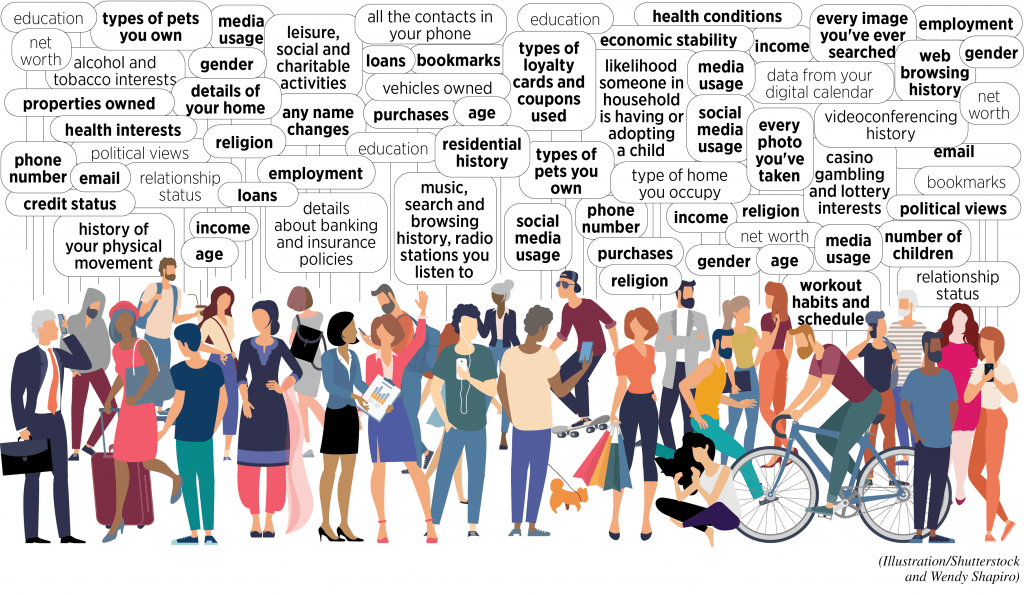

These trackers collect property records, court filings, driver’s license and motor vehicle records, census data, birth certificates, marriage licenses, divorce records, state professional and recreational license records, voter registration information, bankruptcy records, and on and on.

They also collect or buy information from commercial sources, snatching up people’s purchasing histories, including the dates, dollar amounts, payments used, loyalty cards and coupons used, as well as warranty registration information from retailers and catalog companies.

And, of course, they also exchange or purchase information from one another, then merge the data. Most data brokers have profiles on millions of people, each with thousands of characteristics.

“Some would say those companies know you better than you know yourself,” McGinnis said. “And with predictive analytics becoming increasingly sophisticated, they’re getting much better at predicting your next move.”

The Federal Trade Commission took a hard look at the shadowy world of data brokers seven years ago and released a 110-page report in May 2014. But it stopped short of instituting any sweeping regulations—or even requiring data brokers to reveal what they are collecting about whom and with whom they share it.

It is possible for consumers to opt out of some data collection on some sites, but the process is time-consuming, difficult and needs to be regularly repeated because data brokers keep collecting more. Some brokers pull data from other sites and update automatically. And some data brokers don’t remove information even when asked.

People still struggle to understand the nature and scope of the data collected about them. In a recent Pew Research Center study, half of all respondents said they don’t know why their data is being gathered and 9% said there’s nothing they can do to control it.

“Most have no idea who these companies are and how they got their data on them, and they would be very surprised to know the intimate details that these companies have collected on people,” said Amul Kalia, an analyst at the Electronic Frontier Foundation, a global digital rights group based in San Francisco.

The big four

The biggest data gatherers in the game—Amazon, Apple, Facebook and Google—are not in the shadows at all.

The reach of those four behemoths is dizzying. And to expand their reach, the companies have made a multitude of acquisitions.

Collectively, they own websites, operating systems, devices, cloud storage systems and more that gather truckloads of data about you every day.

Google has made more than one acquisition a month for the last decade. In 2014 alone, it purchased a staggering 34 companies. Its acquisitions include YouTube and DoubleClick, companies that expand its reach far beyond its ubiquitous search engine.

Google likely knows everything you’ve ever searched for on the internet, all the apps you use or have ever used, the YouTube videos you’ve watched dating back to 2008, many of the events you attended and when, every image you’ve ever searched for and saved, every location you’ve ever searched and clicked on, and every news article you’ve searched for and read. It also has a five-year history of the photos many people have taken with their cell phones.

And all that information is being constantly monitored, stored and backed up in massive data centers.

It’s not clear how all the data is used—even among data collectors and buyers. Some in the tech sector say the companies collecting the data don’t yet have a use for all the information, but are saving it in perpetuity assuming that technological advances such as artificial intelligence, machine learning and predictive analytics will someday give even the tiniest piece of information value.

The data Google has on most individuals can fill millions of virtual dump trucks. A data collection file on a single person can easily be 5.5 gigabytes, which is 3 million Word documents.

Facebook, meanwhile, collects data on and stores your login location, time and the device used; data on where you are and where you’ve been; what apps you’ve installed (plus when you use them and what for); all the devices you’ve ever used to log in to your account,; all the apps you’ve ever connected to your Facebook account; and every (audio and digital) message, file, emoji and sticker you’ve sent or been sent.

Facebook also collects and stores all the contacts in your phone, what it thinks you are interested in based on the things you have liked and—maybe most eerie—what you and your friends talk about.

The social network monitors and stores information on the games you play; your photos and videos, music, search and browsing history; radio listening habits; and your emails, call history and files you download.

The company also can access your webcam and microphone.

Facebook data on a single person who uses a computer and social media a moderate amount can exceed 600 megabytes, which is 400,000 Word documents.

Many marketing tech companies—a number of which are in Indianapolis—sit on the shoulders of the Facebooks of the world, said Mark Clerkin, vice president of data science for local venture studio High Alpha.

With the vast tech empires controlled by Google, Facebook, Apple and Amazon, chances are that, most of your waking hours, you’re using a device, operating system or website owned or operated—in part or in whole—by one of them.

“If you are using a computer or the web, it’s difficult to get beyond their reach,” McGinnis said.

Listening in

Apple’s 2010 acquisition of Siri Inc. took data gathering to a new level, one that has been elevated by a proliferation of smart speakers and televisions that are always listening.

Introduced in 2011, Siri was touted as an efficient and fun way to search for information. Siri (which has been incorporated into iPhones, iPads and other Apple devices) is a keen listener—even when it’s not being addressed. The same is true for Amazon Echo and Google Home.

“There’s a lot of uncertainty about what the makers of those devices say, and what those devices actually do,” McGinnis said. “The makers of the devices say they don’t track the information.”

DemandJump’s Day isn’t buying it. “How else are they reaching out to you when you are not searching online for something?” he said.

He’s not alone in his skepticism.

“I’m 100% convinced companies are listening to people through devices, including smart speakers and phones,” said Chris Rodgers, a search engine optimization expert based in Denver.

“It’s becoming increasingly common that companies are taking audio and translating that into data and storing it,” said Rodgers, founder and CEO of Colorado SEO Pros. In addition to programming on the devices themselves, he said, many apps can trigger your gadget’s listening device.

“Most of this information is in the privacy policy people agree to,” Rodgers said. “But do most people read those agreements? No.”

There’s good reason companies such as Amazon, Apple, Google and Facebook would want to listen. According to Virginia-based media research firm Comscore Inc., 50% of all searches will be done by voice by the end of this year.

“The technology is certainly there to allow detailed listening-in,” McGinnis said. “This is not science fiction.”

In fact, it would take only seconds, he said, for a smart-speaker maker to pull up audio from a specific hour—even minute—and replay the discussions and other sounds that occurred in your home or office or wherever you have a speaker.

Devices are even talking to one another. TV programmers and advertisers have been quick to enter audio code designed to reach out and message your smart speaker and phone, so they can send you messages or influence searches on your phone or speaker later.

It’s not difficult for a company like Apple, Google or a data broker to figure out which devices are owned by the same person. So when you search for a product with your speaker, you could easily get ads for that or a like product the next time you surf the web on your laptop, tablet or phone.

Location technology

Thanks to global positioning systems—or GPS—and other increasingly sophisticated location technology, big tech companies already know where you are at almost any given time—and with surprising precision. Signals are sent back and forth between one of 27 satellites orbiting the Earth 12,000 miles away and the devices you carry.

Now, technology is in development that is expected to use 3-D models to hone in on where you are within a building.

Google and other companies, tech experts said, will have the capability within a year to know when you’re sitting in bed watching TV. And 5G, with its antennas everywhere, will supercharge the power.

Although GPS data can be and is used to locate you in an emergency, location data is also a valuable commodity. It tells marketers if you are in their area. It also lets them know what you might be doing and what you might be in the mode to buy.

According to a report published by India-based research firm MarketsandMarkets, the location analytics market is estimated to grow from $8.2 billion in 2016 to $16.3 billion by 2021. And keep growing.

Companies like Google and Apple have their own location systems, using information from satellites, cell towers, wireless data points, and even weather and barometric pressure. Users can turn off their location devices by app or through a master control on their phone or device. But even then, Apple, Google and Facebook can gather location data. That’s spelled out in the phone’s privacy policy—which most people never read.

Researchers at Princeton recently discovered a way to track a smartphone’s location—using time zones, air pressure readers and public information from maps—even when all the apps and the master location function are turned off and the phone is disconnected from WiFi.

Lawmakers in parts of Europe and California recently have passed regulations to try to rein in data collectors by adding a level of transparency, requiring companies to disclose how data is collected and how it’s shared.

One result is that people often get a message asking them to allow a website to use cookies. Most quickly click “yes.” If they chose “no,” they often lose some functionality of the site.

But those laws are a long way from becoming widespread. And it’s unclear how data collection will be policed globally.

“It’s not easy to understand how a lot of this works, even for some in the tech sector, and that leads to some of the worries with data collection,” said Peter Lazarz, vice president of marketing for SupplyKick, an Indianapolis-based firm that helps companies set up shop, sell their goods and maintain their inventories on Amazon.

Still, McGinnis said it’s important for consumers to have a basic understanding of data collection and to do what they can to control it.

“People need to think about the technology they use and how they use it, and try to understand how it can be used to collect personal data—and what kind—and weigh the positives and negatives of that before just charging in,” he said.

McGinnis does not use a smart speaker and uses web browsers such as Firefox and search engines such as DuckDuckGo—neither of which collect the reams of data other providers do. He also steers clear of Google whenever possible and closely checks the settings on his electronic devices to limit data collection.

“The legal aspects and regulations are beginning to catch up with this technology, but people shouldn’t wait,” he said. “This is not completely out of the sphere of consumers’ control.”•