Market research contributes to many of the

tactical decisions, but the wealth of new data sources and forms, combined with

various analytics, means MR can meaningfully contribute to more strategic decisions

regarding the products and services being offered. What markets do we enter?

What markets do we exit? What products and services do we add, refine or

emphasise to meet the needs and wants of individuals, households, and firms – and

to grow the business profitability?

One of the most useful structures for

framing product portfolio strategy discussion is market structure or

competitive landscape. What products or services compete with each other, to

what degree do they compete, and why? When populated with historical sales

data, a number of important questions can be answered.

- What product/service segments

are growing faster or slower? - Is the firm’s portfolio aligned

to growth? - How do the firms’ growth

prospects compare to competitor firms? - Where are the greatest new

product/service opportunities, and what size of business can reasonably be

expected? - Are there flanker and extension

opportunities, and for which brands in which product/service segments? - If new products are not a

viable way to enter an attractive product/service segment, what acquisition

targets are attractive?

Approaches

Identifying product/service segments

usually involves some direct or indirect measurement of the degree to which

items are substitutable or similar. Econometric approaches usually involve

price elasticities and/or brand switching. Survey approaches usually involve

simulated trade-offs or measures of perceived similarity. A partial list of

approaches:

- Analysis of price elasticities

based on continuous syndicated sales data - Analysis of brand switching

based on longitudinal purchase patterns - Analysis of claimed past

purchase (survey), often based on correlation or covariance - Sorting into dynamic groups

(survey) - Analysis of brand perceptions,

usually based on survey data

Each approach has its own strengths and

weaknesses, and recommendation is based on context and specific objectives.

A case

study

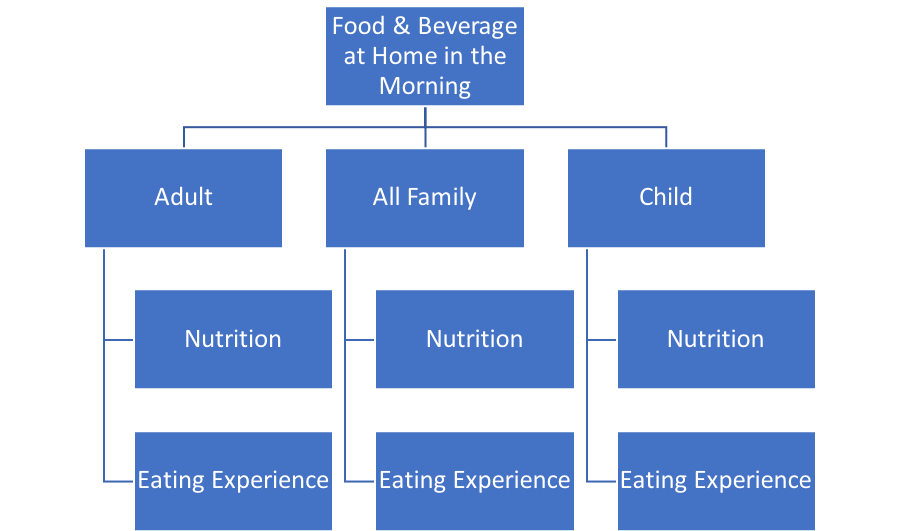

The client is a global food and beverage

fmcg predominantly focused on breakfast and morning eating occasions. Their

syndicated sales databases were organised on the basis of a market structure/competitive

landscape that had been created many years earlier. Consumer tastes and

behaviors had evolved and it was times to update their understanding. A

simplified example might look like:

The most critical project objectives were

to:

- Identify the relevant

competitive structure/product segments in several of their most important

markets, which would then be used to realign the syndicated sales data base - Delineate in detail “how” and

“why” brands cluster into their various product segments, which would ease

transition from strategy to tactics

Challenge #1; a framework that serves both strategy

and tactics

Strategies often fail in implementation

because they are too abstract. In discussions with client, the most attractive

framework for organising detail was brand architecture, and the critical elements

were:

- Target

- Occasions

- Functional benefits

- Emotional benefits

- Key attributes

If brand profiles were available for all

(or nearly all) brands in the respective markets, the key objectives could

theoretically be achieved;

- Brands could be clustered based

on their profiles (in roughly the same way that consumers are clustered in

consumer segmentations) - “How” and “Why” brands are

similar or different would be clear from both the analysis and aggregated brand

profile comparisons

Additionally, a well articulated market

structure, combined with sales data and the appropriate analytic tools, could

answer important foundational questions:

- What elements of brand

architecture are critical to growing existing brands or to creating new brands? - Where do we focus; target,

functional or emotional benefits, occasions?

Challenge

#2; data paucity, especially in developing markets

In the age of big data, data paucity in

certain markets might be a surprise. In developed markets syndicated sales data

coverage might be close to 100%, but in some relevant developing markets it is

less than 50%. Household purchase panel data is typically more limited. Surveys

with large sample sizes could be used to augment, but even here there are issues.

The relatively low penetration of relevant product categories and brands negatively

impacts what can be achieved with either household purchase panel data or

survey data. In some markets the majority of brands have annual penetration of

1% or less.

Merging

multiple streams of data

The solution was found in a qualitative

form of data combined formally and holistically with the aforementioned

traditional quantitative forms of data; a synthesis of syndicated sales,

household purchasing behavior, quantitative survey and qualitative semiotics.

The table below describes the different

data streams, and what each could contribute to informing the brand profiles.

Semiotics

In this case a semiotician interpreted readily

available commercial iconography – packaging, advertising, websites for all (or

nearly all) brands in all markets to infer the various elements of the brand

architecture; who the target is, what the functional and emotional benefits

are, what the occasion is, etc. Semiotic inference was especially useful for

identifying the emotional benefits.

The chart below displays how this works and

how it is validated. The brand is Energen – a breakfast cereal drink that

originated in Indonesia. You can see the inferred target, occasion, and

functional and emotional benefits. Since this is a fairly ubiquitous brand, there

is adequate quantitative data that can be used to validate the semiotic

inferences. Here, the semiotic inference for target and occasion was not wrong,

but it was too narrow; the brand was consumed by a broader demographic across a

wider set of occasions. Across the various markets, this kind of validation could

be done for 10% to 70% of the brands, on various brand profile elements.

Indeed, predictive models could be created for various visual and text icons.

Proof

of concept

Given the forms of data and how they were

merged, proof of concept/validation was important to build faith in the final

product. Brand profiles built semiotically were validated against brand profile

elements from quantitative data where those existed. Some markets had market

structures built recently from household purchase panel data (considered by

client to be the gold standard). Fusion based market structures were compared

to these.

While the deliverable met objectives, attention

areas were:

- one important market failed to

embrace final conclusions because of the inclusion of qualitative data despite

efforts to build credibility - it was difficult in certain

markets to find semioticians - the semiotic coding was time

consuming, but we hope that as AI develops, there will be better ways to “code”

visual iconography

Fusion approaches promise to provide flexible,

holistic, and end-to-end solutions. The key in this case study was a framework

for merging multiple streams of data. While the unstructured data flowed from

semiotics, we think there is opportunity for other forms of unstructured data

such as social media, biometric data, geo-location, and passive metering.