Understanding query syntax may be the most important part of a successful search strategy. What words do people use when searching? What type of intent do those words describe? This is much more than simple keyword research.

I think about query syntax a lot. Like, a lot a lot. Some might say I’m obsessed. But it’s totally healthy. Really, it is.

Query Syntax

Syntax is defined as follows:

The study of the patterns or formation of sentences and phrases from words

So query syntax is essentially looking at the patterns of words that make up queries.

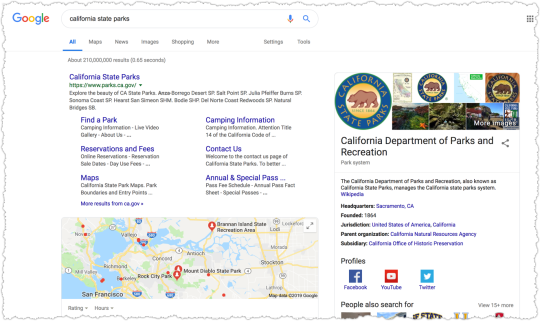

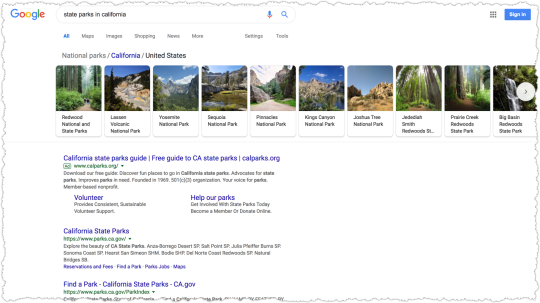

One of my favorite examples of query syntax is the difference between the queries ‘california state parks’ and ‘state parks in california’. These two queries seem relatively similar right?

But there’s a subtle difference between the two and the results Google provides for each makes this crystal clear.

The result for ‘california state parks’ has fractured intent (what Google refers to as multi-intent) so Google provides informational results about that entity as well as local results.

The result for ‘state parks in california’ triggers an informational list-based result. If you think about it for a moment or two it makes sense right?

The order of those words and the use of a preposition change the intent of that query.

Query Intent

It’s our job as search marketers to determine intent based on an analysis of query syntax. The old grouping of intent as informational, navigational or transactional are still kinda sorta valid but is overly simplistic given Google’s advances in this area.

Knowing that a term is informational only gets you so far. If you miss that the content desired by that query demands a list you could be creating long-form content that won’t satisfy intent and, therefore, is unlikely to rank well.

Query syntax describes intent that drives content composition and format.

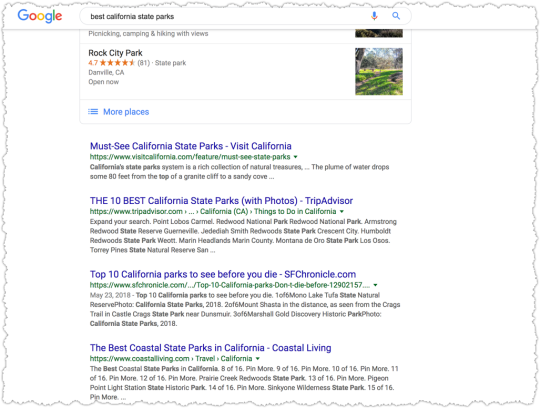

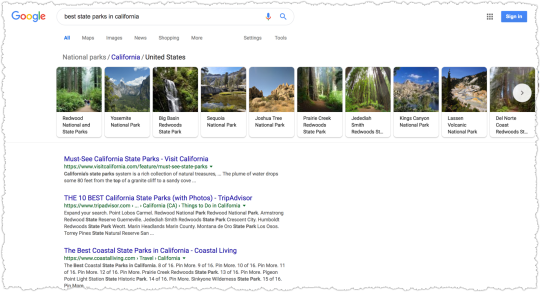

Now think about what happens if you use the modifier ‘best’ in a query. That query likely demands a list as well but not just a list but an ordered or ranked list of results.

For kicks why don’t we see how that changes both of the queries above.

Both queries retain a semblance of their original footprint with ‘best california state parks’ triggering a local result and ‘best state parks in california’ triggering a list carousel.

However, in both instances the main results for each are all ordered or ranked list content. So I’d say that these two terms are far more similar in intent when using the ‘best’ modifier. I find this hierarchy of intent based on words to be fascinating.

The intent models Google use are likely more in line with more classic information retrieval theory. I don’t subscribe to the exact details of the model(s) described but I think it shows how to think about intent and makes clear that intent can be nuanced and complex.

Query Classes

Understanding what queries trigger what type of content isn’t just an academic endeavor. I don’t seek to understand query syntax on a one off basis. I’m looking to understand the query syntax and intent of an entire query class.

Query classes are repeatable patterns of root terms and modifiers. In this example the query classes would be ‘[state] state parks’ and ‘state parks in [state]’. These are very small query classes since you’ll have a defined set of 50 to track.

What about the ‘best’ versions? What syntax would I use and track? It’s not an easy decision. Both SERPs have infrastructure issues (Google units such as the map pack, list carousel or knowledge panel) that could depress clickthrough rate.

In this case I’d likely go with the syntax used most often by users. Even this isn’t easy to ferret out since Google’s Keyword Planner aggregates these terms while other third-party tools such as ahrefs show a slight advantage to one over the other.

I’d go with the syntax that wins with the third-party tools but then verify using the impression and click data once launched.

Each of these query classes demand a certain type of content based on their intent. Intent may be fractured and pages that aggregate intent and satisfy both active and passive intent have a far better chance of success.

Query Indices

I wrote about query indices or rank indices back in 2013 and still rely on them heavily today. In the last couple of years many new clients have a version of these in their dashboard reports.

Unfortunately, the devil is in the details. Too often I find that folks will create an index that contains a variety of query syntax. You might find ‘utah bike trails’, ‘bike trails utah’ and ‘bike trails ut’ all in the same index. Not only that but the same variants aren’t present for each state.

There are two reasons why mixing different query syntax in this way is a bad idea. The first is that, as we’ve seen, different types of query syntax might describe different intent. Trust me, you’ll want to understand how your content is performing against each type of intent. It can be … illuminating.

The second reason is that the average rank in that index starts to lose definition if you don’t have equal coverage for each variant. If one state in the example performs well but only includes one variant while another state does poorly but has three variants then you’re not measuring true performance in that query class.

Query indices need to be laser focused and use the dominant query syntax you’re targeting for that query class. Otherwise you’re not measuring performance correctly and could be making decisions based on bad data.

Featured Snippets

Query syntax is also crucial to securing the almighty featured snippet – that gorgeous box at the top that sits on top of the normal ten blue links.

There has been plenty of research in this area about what words trigger what type of featured snippet content. But it goes beyond the idea that certain words trigger certain featured snippet presentations.

To secure featured snippets you’re looking to mirror the dominant query syntax that Google is seeking for that query. Make it easy for Google to elevate your content by matching that pattern exactly.

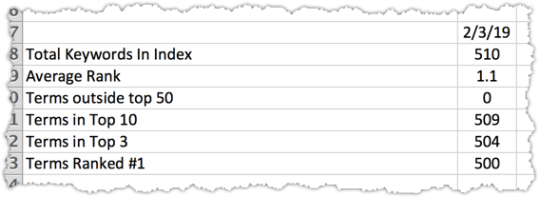

Good things happen when you do. As an example, here’s one of the rank indices I track for a client.

At present this client owns 98% of the top spots for this query class. I’d show you that they’re featured snippets but … that probably wouldn’t be a good idea since it’s a pretty competitive vertical. But the trick here was in understanding exactly what syntax Google (and users) were seeking and matching it. Word. For. Word.

The history of this particular query class is also a good example of why search marketers are so valuable. I identified this query class and then pitched the client on creating a page type to match those queries.

As a result, this query class (and the associated page type) went from contributing nothing to 25% of total search traffic to the site. Even better, it’s some of the best performing traffic from a conversion perspective.

Title Tags

The same mirroring tactic used for featured snippets is also crazy valuable when it comes to Title tags. In general, users seek out cognitive ease, which means that when they type in a query they want to see those words when they scan the results.

I can’t tell you how many times I’ve simply changed the Title tags for a page type to target the dominant query syntax and seen traffic jump as a result. The increase is generally a combination, over time, of both rank and clickthrough rate improvements.

We know that this is something that Google understands because they bold the query words in the meta description on search results. If you’re an old dog like me you also remember that they used to bold the query words in the Title as well.

Why doesn’t Google bold the Title query words anymore? It created too much click bias in search results. Think about that for a second!

What this means is that by having the right words in the Title bolded created a bias too great for Google’s algorithms. It inflated the perceived relevance. I’ll take some of that thank you very much.

There’s another fun logical argument you can make as a result of this knowledge but that’s a post for a different day.

At the end of the day, the user only allocates a certain amount of attention to those search results. You win when you reduce cognitive strain and make it easier for them to zero in on your content.

Content Overlap Scores

I’ve covered how the query syntax can describe specific intent that demands a certain type of content. If you want more like that check out this super useful presentation by Stephanie Briggs.

Now, hopefully you noticed that the results for two of the queries above generated a very similar SERP.

The results for ‘best california state parks’ and ‘best state parks in california’ both contain 7 of the same results. The position of those 7 shifts a bit between those queries but what we’re saying is there is a 70% overlap in content between these two results.

The amount of content overlap between two queries shows how similar they are and whether a secondary piece of content is required.

I’m sure those of you with PTPD (Post Traumatic Panda Disorder) are cringing at the idea of creating content that seems too similar. Visions of eHow’s decline parade around your head like pink elephants.

But the idea here is that the difference in syntax could be describing different intent that demands different content.

Now, I would never recommend a new piece of content with a content overlap score of 70%. That score is a non-starter. In general, any score equal to 50% or above tells me the query intent is likely too similar to support a secondary piece of content.

A score of 0% is a green light to create new content. The next task is to then determine the type of content demanded by the secondary syntax. (Hint: a lot of the time it takes the form of a question.)

A score between 10% and 40% is the grey area. I usually find that new content can be useful between 10% and 20%, though you have to be careful with queries that have fractured intent. Because sometimes Google is only allocating three results for, say, informational content. If two of those three are the same then that’s actually a 66% content overlap score.

You have to be even more careful with a content overlap score between 20% and 30%. Not only are you looking at potential fractured intent but also whether the overlap is at the top or interspersed throughout the SERP. The former often points to a term that you might be able to secure by augmenting the primary piece of content. The latter may indicate a new piece of content is necessary.

It would be nice to have a tool that provided content overlap scores for two terms. I wouldn’t rely on it exclusively. I still think eyeballing the SERP is valuable. But it would reduce the number of times I needed to make that human decision.

Query Evolution

When you look at and think about query syntax as much as I do you get a sense for when Google gets it wrong. That’s what happened in August of 2018 when an algorithm change shifted results in odd ways.

It felt like Google misunderstood the query syntax or, at least, didn’t understand the intent the query was describing. My guess is that neural embeddings are being used to better understand the intent behind query syntax and in this instance the new logic didn’t work.

See, Google’s trying to figure this out too. They just have a lot more horsepower to test and iterate.

The thing is, you won’t even notice these changes unless you’re watching these query classes closely. So there’s tremendous value in embracing and monitoring query syntax. You gain insight into why rank might be changing for a query class.

Changes in the rank of a query class could mean a shift in Google’s view of intent for those queries. In other words, Google’s assigning a different meaning to that query syntax and sucking in content that is relevant to this new meaning. I’ve seen this happen to a number of different query classes.

Remember this when you hear a Googler talk about an algorithm change improving relevancy.

Other times it could be that the mix of content types changes. A term may suddenly have a different mix of content types, which may mean that Google has determined that the query has a different distribution of fractured intent. Think about how Google might decide that more commerce related results should be served between Black Friday and Christmas.

Once again, it would be interesting to have a tool that alerted you to when the distribution of content types changed.

Finally, sometimes the way users search changes over time. An easy example is the rise and slow ebb of the ‘near me’ modifier. But it can be more subtle too.

Over a number of years I saw the dominant query syntax change from ‘[something] in [city]’ to ‘[city] [something]’. This wasn’t just looking at third-party query volume data but real impression and click data from that site. So it pays to revisit assumptions about query syntax on a periodic basis.

TL;DR

Query syntax is looking at the patterns of words that make up queries. Our job as search marketers is to determine intent and deliver the right content, both subject and format, based on an analysis of query syntax.

By focusing on query syntax you can uncover query classes, capture featured snippets, improve titles, find content gaps and better understand algorithm changes.

TL;DC

(This is a new section I’m trying out for the related content I’ve linked to within this post. Not every link reference will wind up here. Only the ones I believe to be most useful.)

A Language for Search and Discovery

Search Driven Content Strategy

The end. Seriously. Go back to what you were doing. Nothing more to see here. This isn’t a Marvel movie.

The Next Post:

The Previous Post: What I Learned In 2018