What is the price of love – £2.00 or £2.50?

‘Roses at Triple the Price’ day is approaching. But this year, particularly for heterosexual couples, Valentine’s Day will be exceptional. 2018 marks the platinum anniversary (100 years) of women receiving the right to vote in the UK. Well, at least 8.5 million women – at the time, forty percent of the total UK adult population.

The Representation of the People Act 1918 gave men aged 21 the vote. Great Britain was still at war so as a concession, men aged 19 on active service could also vote.

Women had to be aged over 30, own a property or married to a man who was a homeowner. Alternatively, they had to be at university or previously studied at one.

If true equality would have been applied, with all women aged over 21 getting the vote, women would have become a larger [proportion] of the electorate than men. And that, historians argue, would have irked too many at the Palace of Westminster.

A decade on, women over 21 became eligible to vote – pushing up the number of female UK voters to 15m.

The lag in equanimity has lingered ever since. From equal rights for gay marriage to equal pay at the BBC.

Recently brand entities such as Formula 1 have been caught up in the race to prove that in terms of sexism, they are politically correct. In Formula 1’s example, they announced they would stop featuring female promotional models at the starting grid – to be replaced by so-called ‘Grid Kids’

Despite Formula 1 reportedly making million pound deals with countries run by repressive regimes that treat women as second-class citizens, F1’s managing director of commercial operations Sean Bratches, said: “‘Grid Girls’ “does not resonate with our brand values and clearly is at odds with modern-day societal norms”.

Of course, for many, the notion of featuring children as ‘Grid Kids’ whips up a completely different set of questions surrounding exploitation.

Whilst society has advanced considerably in 100 years, sadly today for many, festering inequality remains a grit in the shoe. The difference is that channels like social media have given a voice to those discriminated by ageism, racism, class, sexism etc. Equally, it has provided a soapbox to left wing middle classes ever-eager to fly hashtags in support of virtually anybody who shouts loud enough about a suitably marketed cause.

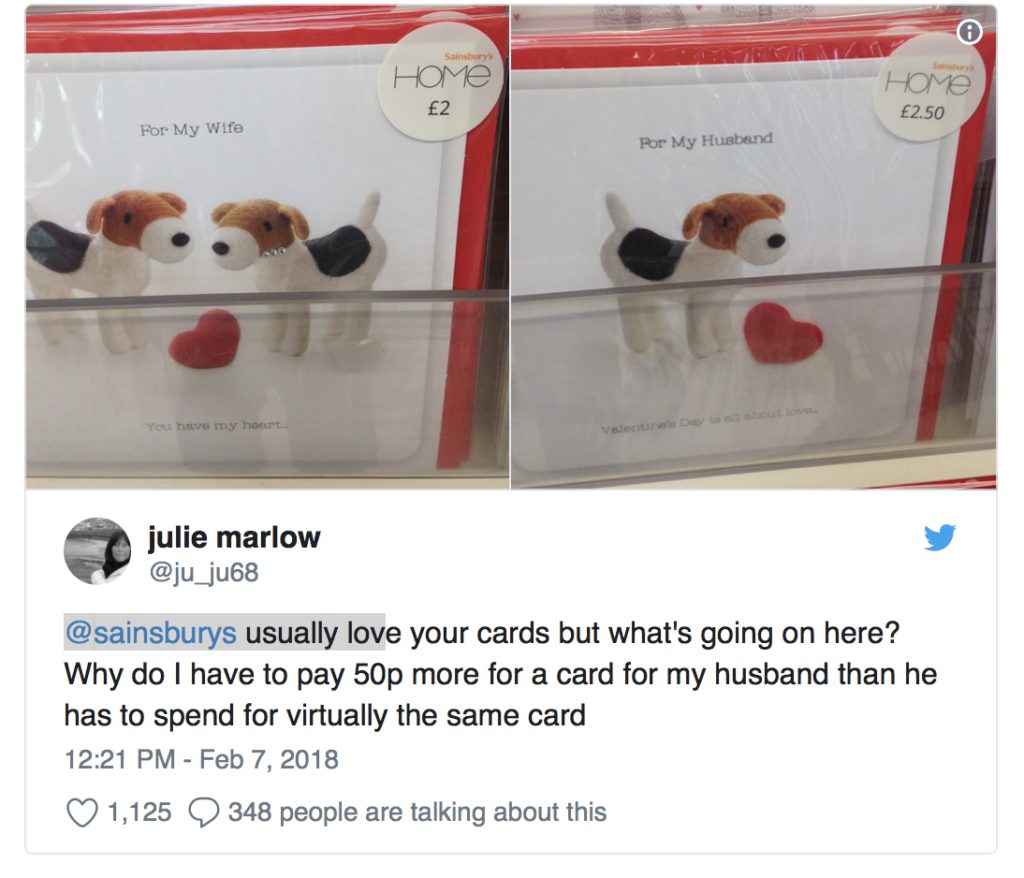

But perhaps one of the most baffling examples of inequality so far this year has no connection to the glamorous world of fast cars, nor the fashionable media.

The culprit turned out to be Sainsbury’s. The retailer was selling virtually identical Valentine’s cards – one from a wife – the other from a husband, at different price points. The Husband’s card cost 50p more than the wife’s equivalent version. (£2.50 vs. £2.00).

The UK greeting card industry is worth an estimated £1.7 billion and is growing. Britons buy an average of 31 cards per year. Roughly £40.2 million of that is spent on Valentine’s Day cards, the highest spend among special occasions.

Dr Panos Sousounis, a lecturer in economics and finance at Keele University, suggested Sainsbury’s pricing could have been caused by assumptions about women’s shopping habits.

“Retailers think women are willing to spend more money on a Valentine’s card, so they price it a little bit higher.”

Following an outcry on social media, the brand announced it would even-out the cards’ prices.

Meanwhile, Morrisons is exploiting Valentine’s Day by selling heart-shaped beef burgers. Normally, the supermarket retails Scotch beef quarter pounders from their premium range for £3.50 (with each burger costing 88p). Whereas a heart-shaped burger costs £1 each.

So it seems that even 100 years after women won the right to vote, some brands continue to ensure that expression comes at a price – in Sainsbury’s’ case – nominally a tariff of fifty pence.

One thing is for certain – assuming global warming hasn’t by then decimated, rose farming – in a 100 years time, I can guarantee that for at least 24 hours in the year, whatever the sex, the price of love will remain that little bit higher.