Results from surveys tracking the true spread of the coronavirus are all over the map—but one done in the heart of the technology sector says the germ is more widespread, and much less deadly, than widely believed.

The new survey looked for antibodies to covid-19 in the blood of 3,300 residents of Santa Clara County, which is home to Palo Alto, top venture capital firms, and the headquarters of tech giants Intel and Nvidia.

According to the study’s authors, which include data skeptic John Ioannidis of Stanford University, actual infections in the region vastly outnumber confirmed ones by a factor of more than 50, leading them to conclude that the pathogen is killing less than 0.2% of those infected in the area.

The Stanford team decribes their work as “the first large-scale community-based prevalence study in a major US county completed during a rapidly changing pandemic, and with newly available test kits.”

Prevalence data like this should eventually provide a big-picture idea of how deadly the respiratory virus is. That is because the larger the number of people whose infections go unnoticed, the lower the death rate may finally prove to be.

The data from antibody surveys, which can find asymptomatic cases, is being closely watched by people eager to draw opposite conclusions—one group saying it will prove that pandemic fears are overblown, and another saying the virus must be fought at every turn.

Nicholas Christakis, a doctor and sociologist at Yale University, calls the effort “a very nicely conducted study with very valuable information [that] triangulates with other data that is coming in.” He adds: “The prevalence is lower than I would have thought, but this is also bad news, since it means that the pathogen has a lot more runway in the area.”

Heart of Silicon Valley

The team recruited volunteers through Facebook ads, pricked blood from their fingers at a drive-up station, and ran the tests in the first week of April. They found 1.5% had immune system antibodies to the virus, meaning they had been infected at some point, even if they had no symptoms.

Taking into account that the tests don’t work every time (they can give false negative results), and correcting for biases in the selection of people surveyed, the team estimated that in fact somewhere between 2.5% and 4.2% of residents have been infected already, or as many as 83,000 people in the county of two million.

Because Santa Clara County had only about 950 confirmed cases at the time, this suggests to them that 50 to 85 times more people were actually infected than appeared in the official tallies, a phenomenon called the “under-ascertainment rate.”

“The population prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in Santa Clara County implies that the infection is much more widespread than indicated by the number of confirmed cases,” wrote the study authors, who were led by population health doctor Eran Bendavid and public health researcher Bianca Mulaney.

The data tell a tale of coronavirus sweeping through the heart of tech country mostly undetected because people either had no symptoms, didn’t see a doctor, couldn’t get a test, or hadn’t yet become ill. The area reported its first case on January 31.

Ioannidis, a Stanford medical statistician and a coauthor of the new report, made waves in March by suggesting the virus could be less deadly than people think, and that destroying the economy in the effort to fight it could be a “fiasco.”

The authors claim their data helps prove at least the first point: if undetected infections are as widespread as they think, then the death rate in the county may be less than 0.2%, about a fifth to a tenth other estimates.

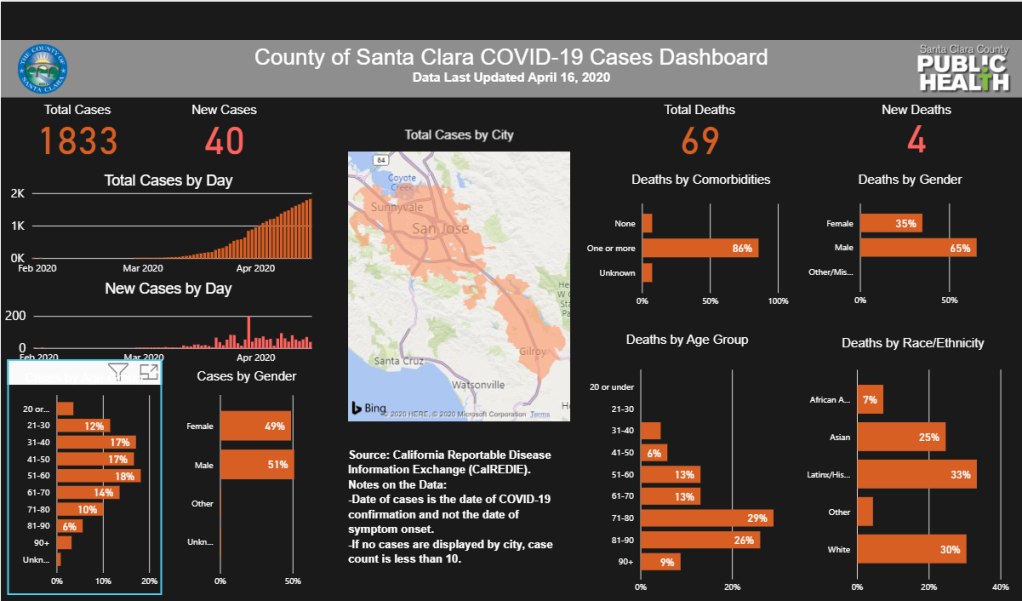

The Santa Clara County covid-19 dashboard shows 1,833 confirmed cases and 69 deaths as of today.

The figures from Santa Clara are roughly similar to the rate of antibodies, or “seroconversion,” in Wuhan, China, where a report described in the Wall Street Journal found that among 8,000 workers and visitors to one hospital, the rate was about 2.5%. That would mean around five times as many people were infected as were officially reported infected in Wuhan, where immense efforts were made to detect and contain the disease.

Many caveats

The Stanford group warns that their conclusions rely on the accuracy of the antibody tests, which isn’t assured. The authors say that if the test they used is less accurate than they think, it could strongly affect their conclusions, or even negate them. People had to be on Facebook and have a car to respond to their ads. And if they were trying to get a test, they might have been more likely than average to have had covid-19 symptoms, which could have inflated the results. The group of volunteers was also skewed toward women and was less than 10% Hispanic, even though this ethnicity accounts for more than 30% of known covid-19 cases in Santa Clara.

It’s also hard to extrapolate from Santa Clara, one of the wealthiest counties in California, to the rest of the country. What we do know is the virus is spreading unevenly: New York City is hard hit, as are vulnerable groups like the homeless, residents of nursing homes, and prisoners. All live in settings that give the virus a chance to take off.

In some places and settings, infection rates are even higher. For instance, in Manhattan, two hospital obstetrics wards decided to test every woman coming to give birth—the 215 expectant mothers were something of a random sample—and found that 15% were infected, though many didn’t have symptoms at the time of testing. They used genetic tests, which are considered the most accurate way to detect current infection but don’t capture those who’ve already recuperated.

A Boston homeless shelter also tested 408 residents, using the genetic tests, and found that infection there was rampant: more than 35% tested positive.

Meanwhile, researchers in Iceland found less than a 1% rate of current infection in the population at large, also using gene tests.

Overall, there are more than 30,000 covid-19 deaths in the US, more than in any other country, so it’s hard to find good news in the blood surveys even if you are looking for it. If the Santa Clara study is accurate and the death rate is lower than many think, it’s still a shocking accumulation of bodies, which explains the extraordinary stay-at-home measures in place in most of the country since March.