It appears that a particular statement that I have been making for quite some time (nearly two decades at conferences in the U.S. and Europe, including SMX) has led to some confusion.

“Do not ever, ever translate your keywords.”

I would say and expect you to understand the nuances I actually had in mind while showing a picture of a prison suggesting you might be incarcerated.

I’m grateful to have the opportunity to put that statement right – and of course, as time passes, the approach itself can change anyway. So let me make a better statement for today’s world…

As Google, Yandex and Baidu have developed their search engines and added more automation, machine learning, AI and sophisticated systems, today’s guidance should be:

“Whatever you do, whatever robot you use, do not in any circumstances use any kind of system to translate your keywords – or you will be sent straight to jail without passing go.”

There. Now I feel much better – but first let me dig into the topic and explain why that is still the case.

Firstly, we need a definition for “keyword,” which is tricky.

“A keyword is a concept someone uses for an answer to something that is on their mind and commits that keyword by text or speech to a search engine in a quest for a relevant answer to their query or question.”

You’ll note that we now have to include voice search and the impact of speech.

Secondly, we do need to look deeper at that word “translate” which is where I was at my most confusing. In this context, a translation is a conversion of the mean of the phrase or words in the keyword into another language – using translation systems, dictionaries or simply by knowing both languages.

So why is translation a problem? Let’s stick with American and British English to understand this one. A colleague of mine recently described a childcare situation where a young child was asked to make sure to change their pants – meaning those long garments that go from waist to ankles of both legs. In the UK, we call those “trousers.” The child began to change what they understood to be “pants” and it wasn’t their “trousers” but the undergarment that we Brits indeed call “pants.”

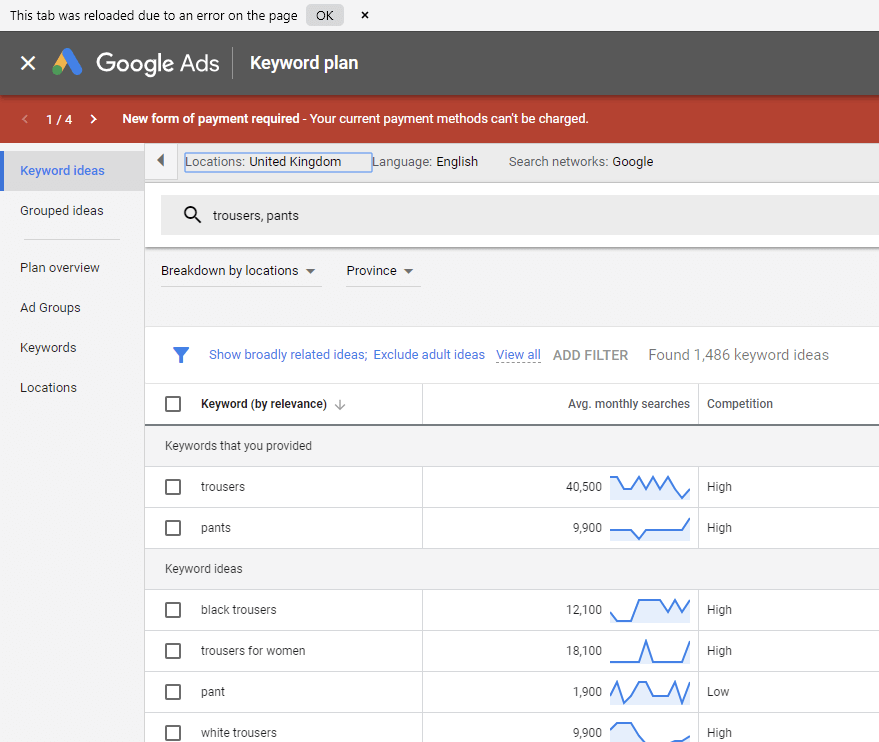

The above image from Google Ads successfully illustrates the data trap we all suffer from. You look at the “trousers” and “pants” data and start to say, well yes trousers and pants are both searched for in the UK with trousers ahead. See! You’ve forgotten already that pants in the UK are a completely different object.

The first problem for translation is that we can have different variations of the actual intended meaning of a word and different speakers can have different intentions in mind. While I’ve given you an entertaining example, the language of commerce is highly complex and such variations can exist between workers at one company and another in the same industry – and the users may be using a completely different language. Translation at this point is going off on a tangent and nowhere near the intended meaning.

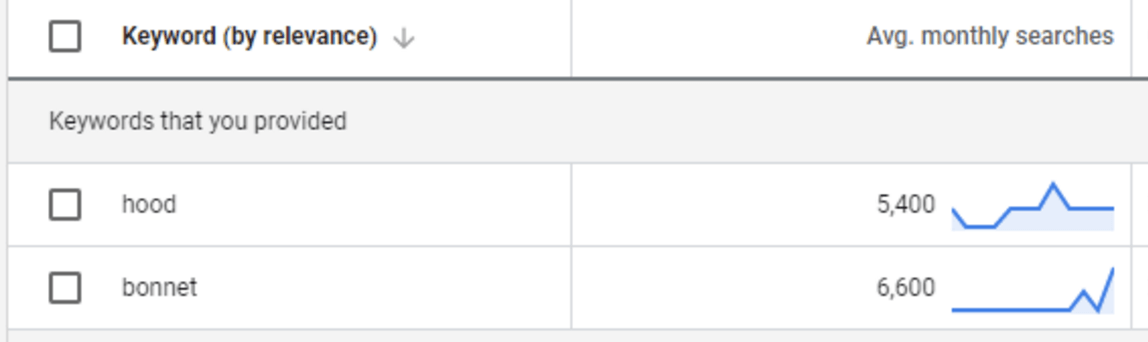

Another example might be to look for a replacement “hood” for my car. That would work in the US – but in the UK I’m going to get something that Red Riding Hood might have worn rather than something to cover my engine.

For the UK there is more emphasizes there are searches for both hood and bonnet in the UK. A good way to check what these words actually mean is to go to Google images – in the UK, there are only pretty little bonnets covering car engines.

The next problem with translating keywords is that in a different language the name given to something may well relate to a different history of things. Living in Spain, I know that acronyms of three letters become spoken words. So, for instance, a Spanish domain name is known as a “punto-es” where “es” is pronounced as “yes” without the “y” rather than a “punto-e-s” which would be the translation of “dot-e-s.”

Keywords in Spanish are known as “palabras clave,” which is curious because your keys are called “llaves.” This is an example of the second big issue with translating keywords – homonyms. A homonym is a word which has more than one meaning, but the same written word is used (homophones can also exist which may be written differently but sound the same).

Languages acquire words from their histories, descending from Latin or other influences. Speakers who use those keywords make them up. Yes you heard that right, search engine users are making up the keywords they use to search with – they’re using the words they think will get them the right answers. In this, the search engines train the users to adopt certain keywords as a result of trial and error – but even this trial and error is dictated by the language of the content searched for.

The other curious thing about keywords is that they are heavily led by voice – even the keywords that are typed – and this has always been the case. But voice search makes the translation of keywords even less likely to be successful. An American searching for “pants” does not look up in the dictionary the word for the garment worn knows it through the experience of talking about it because word of mouth is a very powerful driver of the development of keywords. Your mother is more likely to tell you to get your pants on than to send you an email about it.

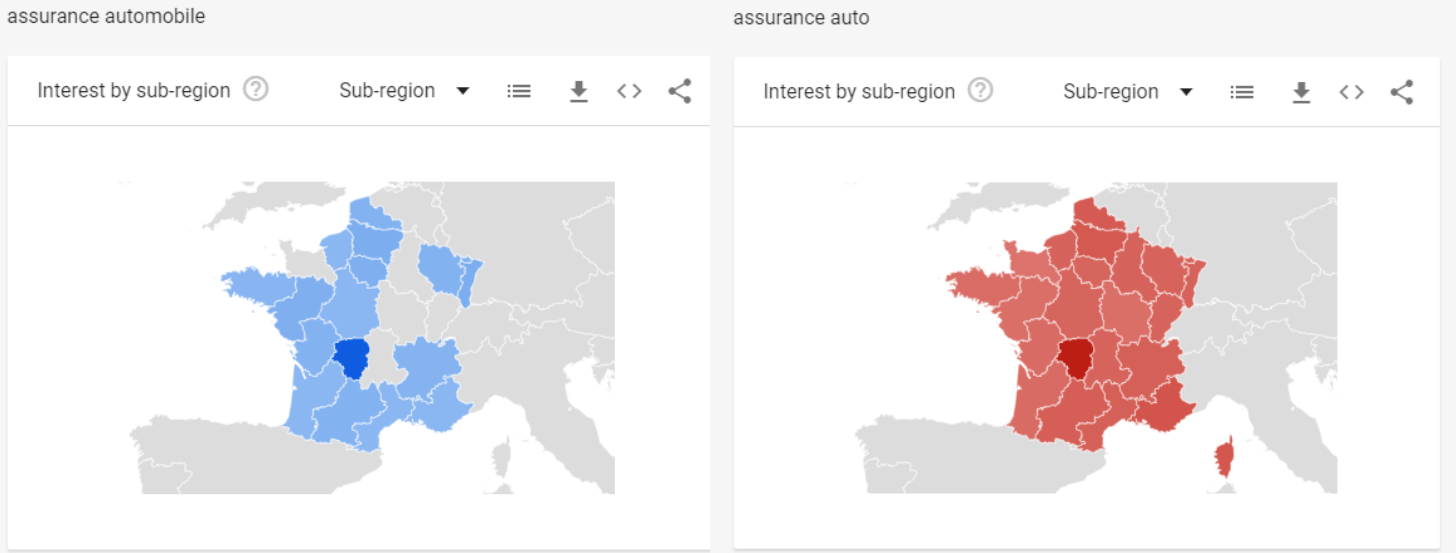

French consumers search for assurance voiture, assurance automobile and assurance auto. Assurance automobile is considered by Google a close variant of “assurance auto.” By comparing regional search volumes in France you can see that “assurance auto” is the stronger keyword with a wider geographic strength.

And therein lies another part of the problem. Translation systems and their various pieces of automation are heavily led by the written language. Yet when we speak, we abbreviate to clarify our meaning. So for, instance, “car insurance” may indeed be translated as “assurance voiture” or “assurance automobile.” However, French search engine users tend to search for “assurance auto,” which is derived from speech. The translation systems may connect car insurance with the two different French terms available (but the translator is forced to use one for the content) but the speech-derived version is unlikely to appear on your list.

So, what’s the solution? Trust in data-driven research with a native speaker. Keywords remain the building blocks of all search, so taking shortcuts on keywords is a recipe for global catastrophe – and we wouldn’t want that.